Curator’s essay: MUNCH Triennale – Almost Unreal

Learn more about the artist and their works in the second edition of the MUNCH Triennale.

Alice Bucknell, Earth Engine, 2025. Med tillatelse fra kunstneren

The title of this second MUNCH Triennale, Almost Unreal, refers to a state of in-betweenness. The combination of the words “almost” and “unreal” points to something that is neither real nor virtual. It actually resists such either-or binaries: reality or illusion, actual or fictional, historical fact or mythological invention. Rather, it embraces shifting states of almost unreal. In this way, it carries on the queer curatorial approach of the first MUNCH Triennale, which similarly rejected a binary view of new technology as either dystopian or positive, seeing it instead as a spectrum and a device for asking “what if?”.[1]

Many contemporary artists’ practices move along a spectrum of un/reality. It is a long time since art’s primary purpose was to imitate reality; today, it makes new realities and builds alternative worlds. Developments in technology, particularly in gaming, mean that realistic landscapes and figures can easily be created. “Unreal” is both the name of a well-known game engine and 3D creation platform and is an expression of admiration – Unreal! – as if transcending reality is the highest accolade. The hyperreal – simulations that appear more real than reality – has seeped into everyday life as AI-generated imagery and various filters and enhancement tools are readily available on handheld devices.

With seemingly infinite power “to make new” such acts of making-over nonetheless remain close to the reality of IRL – in real life. The past – whether as lived experience, fiction or somewhere in-between – is still mined for its stories, symbols and motifs. This applies both to human art-making and to generative artificial intelligence touted as creating original content. However, where the latter is derivative, in my opinion, the former draws on complex webs of knowledge, association and material exploration, which can trigger the viewer’s own sense of imagination to much greater degree. For me, this is the key role of displaying art in 2025.

When she received the Holberg Prize in Bergen in June 2025, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, thanked the director of the prize for an “unreal introduction”.[2] In her ensuing lecture, ‘Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Future’, she referred to a crisis of imagination and the importance of training it through literature, philosophy and conceptual art. I agree with Spivak: We have become slaves to algorithmically generated content centred on consumption and self-improvement and can easily waste hours doom-scrolling. What is at stake is our ability to conceive of alternative futures, to escape current despair and malaise. Art cannot solve the crises we find ourselves in, but it can cultivate our abilities to slow down, complicate and imagine differently.

The song Almost Unreal by Swedish pop duo Roxette from 1993 kept playing in my mind as co-curator Mariam Elnozahy and I were working on this edition of the Triennale. Despite its earworm potential, the song is not one of their greatest hits. I failed to make Mariam a fan. The band themselves apparently did not even like it.[3] It came to me because a friend saw a Roxette LP being thrown out and decided to rescue this guilty pleasure of mine.

Other coincidences seemed to cement the title. Almost Unreal by Roxette was originally commissioned by Disney for the film Hocus Pocus (1993) but was bumped in favour of a track by En Vogue. It was repackaged for another Disney project, Super Mario Bros. (1993), starring Bob Hoskins and Dennis Hopper as the brothers Mario and Luigi. This was incidentally the first American feature-length live action film based on a video game. It was a financial flop at the time, yet the film has developed a bit of a cult following. Having watched it in 2025, I would not say it has aged well. Rather, it has aged so much that it seems strangely cool now, over 30 years later. Certainly, its 1990s sci-fi typeface with a shiny 3D-effect has inspired the graphic design of the MUNCH Triennale. It dovetailed with the desire Mariam and I shared to explore 'older' technologies in this edition of the Triennale. From such a random starting point, Almost Unreal remained a possible title. As we discussed the selection of artists for the Triennale, we painstakingly whittled hundreds down to about 20 different projects.

The hologram was one of these older technologies we were initially drawn to. Invented in 1947, it continues to generate a sense of wonderment that remains to this day. The hologram refers to something that is both present and a mirage at the same time. It has been used to bring musical artists back from the dead – including Tupac Shakur, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston – and even to let living musicians turn back time (another guilty pleasure song of mine). In an essay in Norwegian newspaper Klassekampen this summer, writer Karl Ove Knausgaard described the Abba avatars at a recent concert in London as “consisting of light, but seeming alive, emerging from a platform under the stage, as if from the underworld, singing.”[4] Whilst such mega-commercial musical events are a relatively recent phenomena, the hologram has been used by artists since the invention of holography, and they feature in the Almost Unreal in different forms. The hologram also has wider application and has been used as a model for rethinking reality in scientific theories emerging from quantum physics. The “holographic universe theory”, launched in the early 1990s, proposes that we are, in fact, living in an image constructed by the human mind.[5] A more recent, parallel theory is that we are living in a computer simulation.[6] The hologram, therefore, became an apt articulation point for thinking about technology, presence and reality through the exhibition.

The second edition of the MUNCH Triennale includes 26 artists. At the time of writing this text, about half their works have been completed. None of them have been installed. This is the predicament of any curator trying to write about an exhibition that has yet to assume physical form in a particular place at a particular time. With triennials and biennials, there is an expectation that visitors will experience something novel, not just in the constellation but in the creation of new artworks. Both Mariam and I have taken great pleasure in commissioning new works from artists, being part of the conversation as the work develops. Over the course of building, composing, filming, editing and assembling artworks artists make changes. That means at the time of writing that there is a certain amount of guessing going on. In this essay all quotes are taken from work descriptions from artists in written or verbal form. Even works that were made a long time ago and have entered private and public collections with set dimensions, material descriptions and accession numbers suddenly fall foul of soaring transport costs, import or travel restrictions, and are hastily replaced by another. Machinery for making and presenting the work can break down, leaving an exhibition ostensibly about technology paradoxically thwarted by it. With these provisos – some more realistic than others – I will proceed to provide potentially inaccurate descriptions of these rich, diverse, thoughtful, funny, confounding, poignant and magical works in Almost Unreal.

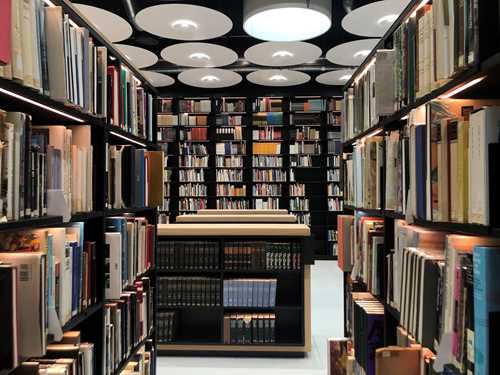

Alice Bucknell is one of the artists who has made new work for the exhibition. Their Earth Engine is a walking simulator, a type of video game in which the primary form of interaction with the environment is walking, rather than combat or extraction. The human visitor to the game is cast in the role of a non-player-character, turning the regular hierarchy of video games on its head. As Bucknell notes, “walking sims” tend to displace agency in the game into the narrative or the landscape by asking players to grapple with failure, the limits of (human) agency, and the affective capacities of gaming in novel ways. Earth Engine makes use of GIS (Geographic Information System) tools and other climate modelling projections to create a world that is unique with every play-through. Like other walking sims, Earth Engine, has ecological and queer undertones, and rewards slowing down and paying attention. Bucknell questions the limits of predictive technologies, mapping and modelling and how they foreclose other possible futures. In their work, Bucknell combines digital, offline, natural, and built environments into a web of mutually contingent relationships.

Ann Lislegaard’s practice has a similar concern for non-human beings. In her work for the MUNCH Triennale, In the Shadow of Trio A, a spider moves with great precision in a post-apocalyptic landscape in which only insects have survived. The spider is performing sequences from Yvonne Rainer’s choreography The Mind is a Muscle, Trio A from 1966, an assemblage of gestures and ordinary movements Rainer had gathered through observation. Like Bucknell, Lislegaard displaces the human at the top of the hierarchy, commenting that “the spider's performance can be seen as an unfamiliar reversal of our own endeavours to remember and commemorate the many species of animals, plants and insects that have disappeared.”

Atithi means “guest” in several Indian languages, including Sanskrit and Hindi. In Sahej Rahal’s new work for the MUNCH Triennale it is the name of an audio-responsive artificial intelligence. It is part of a series of AI simulation programmes Rahal has created in recent years in which “indeterminate beings begin to emerge from the cracks between the real and imagined.” The titular character, Atithi, is a cluster of tentacles who moves in a gaming environment, set in an abandoned and overgrown temple site. Through small contact microphones, the creature picks up ambient sounds in the exhibition, which it responds to. As Rahal comments: “Through a multisensory interplay of sonic and haptic feedback, Atithi orchestrates a dance of cognition, across the porous boundaries of myth, machine, mind, and memory.” Breaking out of the screens, Rahal’s installation also features two 3D-printed sculptures: Atithi in ossified form, made palpable and three-dimensional. A rebuke to the notion of technological intelligence and a computational view of the world is something Rahal’s work shares with that of Bucknell, whereas the creatures’ dance finds resonance in the movements of Lislegaard’s post-apocalyptic spider.

Dancing is central to a number of works in the exhibition. A touchstone, and one of the first artists Mariam and I selected was Simone Forti, based on her holographic works from the 1970s. Working with physicist Lloyd G. Cross, Forti found a way to use technology as a way of performing her choreography without the dancers being present. A piece like Huddle exists both as a score to be performed, a video work and a 200-degree multiplex hologram, meaning that the image changes depending on which angle it is viewed from. Huddle is part of Forti’s Dance Constructions series and originally premiered in 1961. In it, a group of up to ten performers climb and break away from the eponymous huddle, creating minimal moving sculptures over a 15-minute period. Whereas holography is a relatively simple technology that relies on light to create an image, multiplex holograms are more elaborate and complex to create. In the case of Huddle, a filmed sequence was transferred to holographic film, which in turn was laminated onto a curved sheet of translucent plastic. An electric light source in the centre of the “multiplex” conjures up ghostly images from the choreography as viewers move around the work. With its small size and ethereal light, the multiplex hologram adds a sense of wonderment.

A similar “magic of scale” created with simple and by now “old” technology can be found in Icaro Zorbar’s work The Pace of Time. A reclaimed oak table becomes the site for a collaged choreography for hacked machinery, patinated by time. Here a tiny ballerina, projected onto a small piece of paper, performs pirouettes that echo the spin of a trompo, a children's toy which has existed for over 6000 years. Simultaneously, a revolving turntable plays an LP with the sound of several old music boxes. Their deconstructed mechanisms, also on display, hint at the sound's origin while resembling miniature Minimalist sculptures. Exposed cabling, motors and uncased mini-projectors reveal how the different components are connected. Perhaps paradoxically, this rejection of illusionism, the refusal to hide the nuts and bolts, gears and wires, amplifies the sense of enchantment.

Forti and Zorbar’s work illustrate this exhibition’s emphasis on “old new technologies”, which includes several textile works. The jacquard loom famously prefigured computing through its use of punch cards – a binary system that anticipated the digital logic of zeros and ones. For example, in a lecture at the Vera List Center in 2020, writer, professor and computer programmer Alexander R. Galloway referred to “the algorithmic nature of weaving and the woven nature of algorithms.”[7] Kristina Austi’s digital jacquard weaving, The Game of Life, features a grid pattern, resembling of pixels. The title is taken from mathematician John Conway’s zero-player “game”, aimed at creating a so-called “universal cellular automaton”, which could be used to create simulations and models for all manner of phenomena. When it was initially published in Scientific American in October 1970, Martin Gardner wrote, “Because of [Conway’s] Life's analogies with the rise, fall, and alterations of a society of living organisms, it belongs to a growing class of what are called 'simulation games' (games that resemble real-life processes)." A simulation can be an abstract complex “second life” lived in a parallel universe, online or otherwise, but it can also be a simple, analogue representation.

A related and perhaps more common association with the title is the boardgame turned video game The Game of Life, which simulates a person’s journey through life. The game adheres to a highly heteronormative and capitalist logic: there are two sexes, demarcated in pink and blue; the game rewards financial accruement, getting married, acquiring children with the expressed aim of reaching wealthy retirement. In Austi’s weaving, the rules of the algorithm and such colour-coded logic are rejected in favour creating the pixel pattern manually, asserting kinship with methods and motifs that are, as she writes “so typical in many cultures and found in textile designs all over the world.” Installed against a wall that picks up the colour of some of the individual “cells” in her design, Austi inserts a smattering of psychedelia into the age-old symbol of the eight-pointed star that dominates the design.

There are clear links between Austi’s work and that of Nanna Debois Buhl, and not only in the fact that her works were produced by Austi on her industrial jacquard loom at Vevft, an artist-run centre for digital weaving, located in the small town of Innvik on the west coast of Norway. In her PhD project, Debois Buhl “investigated how visual perceptions of the cosmos have influenced our worldviews over the past centuries” displaying a similar interest to Austi in longer historical lines and the relationship between art, craft and science. In LUNAR Debois Buhl translated the first images of the far side of the moon to a digital jacquard weaving.

The Soviet Luna 3 spacecraft made the far side of the moon visible for the first time in 1959, through 17 photographs, which were scanned and transmitted to earth, line by line, much like the threads of a jacquard loom. Whereas the near side of the moon could be observed from earth, the far side – sometimes referred to as the dark side – had remained a mystery up until then. For centuries, the moon had been a site for speculations on alternative societies. Debois Buhl uses the example of 1662 engraving entitled Carte du Monde, which portrays the moon as a series of kingdoms run by women in which mountains and craters attributed to various emotional states.[8] The moon’s role in affecting moods is evident both in the etymology of “lunatic” and across different cultures that believed that there was a goddess of the moon, including the Roman Luna, the Inca Mama and the Chinese Chang’e. Space exploration and its photographic evidence was not only a killjoy of such age-old speculation but came at a gigantic financial cost.

In another connection between the three textile projects in the Triennale, Debois Buhl explicitly cites Charlotte Johannesson, noting her early experiments with computers and weavings. Johannessen’s weaving practice began in Malmö in the South of Sweden in the early 1960s and Norwegian textile artist Hannah Ryggen (1894–1970) was a great influence. Johannsson’s forays into digital art and computer graphics began when she acquired an Apple II Plus in 1978, one of the first generation of personal, so-called “micro-computers”. From a vast oeuvre comprising digital works, prints, painting and weavings, three of her textile works are included in the MUNCH Triennale. The earliest, Terror from 1970, is a collage made up of linen, wool, leather, pins, needles, wire and a pencil sharpener. It was made in response to the attempted assassination of the German leftwing student activist Rudi Dutschke. Like many of her woven works, it has been lost and was reproduced in 2016 by Tiyoko Tomikawa. It shows Johannesson’s penchant for slogans that sum up the zeitgeist, often accompanied by figures made up of pixels. Coined in the 1960s, “pixel” is an abbreviation of “picture element” and is the smallest component of a digital image. For Johannesson, there was a clear link between the loom and the computer screen, which she described as “synchronicity”, both being made up of 239 x 191 pixels.[9] As Debois Buhl commented: “Aesthetically and technologically, Charlotte Johannsson’s weavings thus connect thread and pixel, and this connection is reinforced in their visual language in which small square units are playfully organized, enlarged, and exaggerated.”[10]

A later work, No Future from 1977, is handwoven and shares its name with the Sex Pistols song of the same year, echoing the influences of punk on Johannesson’s practice.[11] The final textile work has a more aspirational slogan, taken from Emily Dickinson poem from 1896. The Brain is Wider than the Sky (2019) is digitally woven and draws on earlier works in other media that feature lines from the same poem. It is the final work of the Triennale on the Level 3 galleries at MUNCH, acting as a reminder of the power of the imagination. It bookends the first work of the Triennale, one of Johannesson’s digital works that greets visitors to the museum with the rallying cry “take me to another world”. The exhibition is a device that invites myriad ways of thinking through artworks, and the hope is that it broadens the mind, perhaps not to the extent of making it “wider than the sky”, but Johannesson’s slogan is nevertheless an apt aspiration.

Both Debois Buhl and Johannesson’s work deal with the power of imagination. In Sara Sadik’s work, the same urge to project into the future is grounded in the present day, amongst a community of teenagers from the Seine-Saint-Denis neighbourhood in Paris. This area on the northeastern outskirts of the city is often described as the most deprived in France. Her work 80 ZETREI Summit evokes the title 2015 song by famed French-Ivorian rapper Kaaris, which depicted the area where he grew up as characterised by guns, gangsters and drugs, but with a tight-knit, diverse community. The summit that Sadik has staged takes place in the Espace Niemeyer inaugurated in 1971, the headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris. Filmed in 360 degrees, the teenagers come together to speculate on the future, and the kinds of systems and infrastructures they would like to institute. Like Rahal’s work, this four-channel video spills out into physical space with its inflatable seating, a thick, organic shape that echoes the curvature of Oscar Niemeyer’s architectural forms.

As a way of escaping the two-dimensionality of the flat screen, several works in the MUNCH Triennale similarly spill out and command the space in their immediate surroundings. One of the largest installations, Patch Opal, is a new commission by Infopsin, a group of visual artists comprised of Ayatgali Tuleubek, Ignas Krunglevičius, Ragnhild Aamås and Istvan Virag. Their video installation consists of large, curved LED screens set in a grid structure. Having motion-captured humans engaged in Live Action Role Play (LARPing), they have used Unreal Engine to translate the live action into a gaming environment. The humans dance and cavort in a post-apocalyptic landscape that is based renderings of the museum and its surrounding Oslo fjord. It evokes both the abandoned temple site of Rahal’s Atithi and the dystopian landscape of Lislegaard’s dancing spider. While the structure echoes the pixels of the screens, the screens themselves echo curvature of the retina of those watching the film, like a giant eye looking back on the viewer. With its sheer size, it invites a different kind of engagement to the meticulously small works of Forti and Zorbar.

Nearby, Emilija Škarnulytė’s new installation continues her exploration of the slippages between hydrology and mythical sea creatures. Baltic amber from around the seas of Northern Europe has spawned many stories of its origin, including claims that it comes from the tears of mermaids. Škarnulytė’s teardrop-shaped sculptures draw on this myth as she creates a closed installation with a projection of a slow-moving eternity serpent, flanked by sculptures whose ethereal glow is reflected in the shiny black vinyl floor. Škarnulytė’s work continues beyond the level 3 galleries at MUNCH, traversing several floors with a long textile print. Against the backdrop of the surrounding Oslo Fjord, it provides a diaphanous layer to the view. Light passes through strange subterranean creatures depicted on the textile, a kind of primordial soup that predates the establishment of the city by several millennia.

Patricia Domínguez’s work similarly draws on myths and what she refers to as “spiritual technologies”. Trained in botanical illustration, Domínguez has a deep interest in ethnobotany, the scientific study of plants and their medical, religious, ritual and other uses in the traditional knowledges and customs of different communities. In her new constellation of watercolours in the installation Three Moons Below for the MUNCH Triennale, a structure of MDF “totems” holds speculative imagery of the interconnectedness of the mind and interplanetary energies. The structure is backlit with LED strips, giving its contours a shiny glow that adds to its altarlike appearance. A mechanical bird looks on, referencing Domínguez’s engagement with interspecies relationships, whereas the green computer motherboard, inset with gemstones, evokes the technology that she seamlessly weaves into her practice and its reliance on rare earth minerals.

In the MUNCH Triennale, Domínguez’s installation is placed opposite that of the duo Mazenett Quiroga, comprised of Lina Mazenett and David Quiroga. The resonances between their Motherboard/Motherearth installation and Domínguez’s Three Moons are manifold. There is a direct visual resemblance between Domínguez’s one watercolour of a green computer motherboard and Mazenett Quiroga’s sculptures based on actual reclaimed computer parts. All three artists also share an interest in the intersections between science and mythology, so-called Western epistemologies and cosmological, ritual, and Indigenous knowledge. The design of Mazenett Quiroga’s sculptures are based on Indigenous ritual objects in Bogotá’s Gold Museum. Citing anthropologist Johannes Neurath, Mazenett Quiroga regard these ritual objects as technologies in the context of cosmopolitics – the idea that politics extends beyond human affairs and encompasses the entire cosmos – and see the installation as an “archeology of the future”. The colonial context in which the Gold Museum acquired these objects hovers in the background, as does the extractionism associated with both the gold objects in the museum and the rare earth minerals in the computer’s components.

Natalie Paneng also describes her new installation, Didirišwa Tša Bogologolo (Tools Of The Past) as an archeology of the future. Seven “technological relics” sit in a recycled museum vitrine. They are sculptural hybrids of soil, minerals and obsolete electronic devices, like the Tamagotchi, the digital pet launched in 1996. Opposite the vitrine, a four-channel video plays across screens set in what resembles neolithic stone constructions in an altarpiece formation. The seven displayed objects feature in the film. Paneng departs from West-African elder, writer and teacher Malidoma Patrice Somé’s notion of “indigenous technology” – practices and knowledge systems used by his Dagara tribe to maintain harmony with nature and each other, often involving rituals, divination, and healing practices.[12] As she writes, “Technologies in the Indigenous world are developed to fulfil fundamental human needs, such as fostering community, promoting health, cultivating harmony, and providing a sense of meaning and purpose in life.” Somé’s writings are also a key reference for Patricia Domínguez, adding to the sense that these respective works evolve from a similar spiritual-conceptual domain.

The enduring influence of the past is central to Priyageetha Dia’s work, Spectre System (2024). It centres on the landscape of a plantation on the Malay Peninsula, once part of the British Empire and subject to colonial extraction and indentured labour. A key theme in the work is how disembodied labour persists today. In the video, the titular spectral orbs float and flicker with a bluish white light. Dia refers to them as Inaivu, a name that merges the Tamil word ninaivu and the Malay term ingatan, both meaning “memory”. They are “beings of remembrance” that roam a landscape that is itself a living entity. As the narrative of a new reality, consisting of intangible realms of digital labour and a hyper-globalised economy unfolds, AI-generated imagery is produced using the deep learning model Stable Diffusion, which converts text to images. The final part of the installation is a large vinyl print of rubbery, contorted hands that envelop the video. According to Dia, “they gesture toward the ghostly residues of labour, tracing how its impact lingers across temporally, spatially, and materially, imprinting itself onto the lived conditions of the present.”

The spectral presence of colonial exploitation also features in Himali Singh Soin’s work in the MUNCH Triennale. how to startle the unbelieving (2019) is a poem in the form of a minimal video of a pair of hands that seem to hover, disembodied in the darkened space. The voice-over narrates a story that Singh Soin discovered in the archives of the Bombay Monthly Times from 1850. It describes a young girl from Calcutta who was rumoured to have clairvoyant capabilities. In a well-publicised expedition, British explorer Sir John Franklin had failed to return from his search for a Northwest Passage. His wife enlisted the girl to act as a portal to the Arctic to help locate her husband and his two ships. Singh Soin describes the girl as an “early cyborg” and a medium between the British Empire and its colonies.

The notion of clairvoyance also features in the new work of Natasha Tontey. In her film, Macho Mystic Meltdown: Oikouménē, the main character is her own father who, in her words, is “living on the boundary between the real and the virtual”. After being stranded at sea for several days in the 1990s, he became a stay-at-home hoarder, conspiracy theorist and follower of many different religions, strangely apart from the teachings of his own Minahasan heritage. In Tontey’s film, a phone found amongst the detritus he has collected over the last 30 years acts as a portal to another world which can “commune with spirits, UFO travellers, the departed.” In this alternate world, filled with trinkets and junk, minor characters include a dolphin, a rag doll and a troupe of drag queens. Their glamour is echoed in an oversized vanity mirror framing the film screen, while the audience’s seating gives the generic impression of a waiting room.

Whereas many of the artists in the MUNCH Triennale create landscapes rendered through digital tools, like Unreal Engine or Stable Diffusion, Sven Påhlsson’s virtual representation of a woodland scene in Finding Bambi (2023) is handmade. Finding Bambi is modelled on an existing place, Dalsfjorden on the Westcoast of Norway. The ensuing film clearly resembles a real forest, though the point of view of the “camera” is odd as it glides diagonally up the forest as if it was attached to a slow cable car or drone. The light as it hits a moss-covered tree stump is almost ethereal, creating different shades of green. The constructed sunlight draws the gaze up beyond the frame of the video in search of its celestial source, whereas the illusionary ambient soundtrack creates a sense of being in an otherworldly clearing.

The act of hacking is also a form of handmade labour. In his new film, Dreamcore, part of the series Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another, Firas Shehadeh creates glitches and disruptions in the video game Grand Theft Auto V. Drawing parallels between the fictional city of Los Santos in the Grand Theft Auto universe and his native Palestine, hacking enables imagining another world for colonized people. Shehadeh cites dreaming as a defiant strategy of resistance, which is often dismissed by settler logic as irrational. However, to the indigenous inhabitant it is a source of truth, one that acts as both an archive and a vision. As Shehadeh writes “It imagines a new world, one that overwrites the colonial vision with the native's dream. Here, to dream is not to escape, but to defy”.

Dreaming of alternative futures through worldbuilding in gaming environments is also central to Keiken’s ongoing work, Morphogenic Angels. The trio, consisting of Tanya Cruz, Hana Omori and Isabel Ramos, have been working together since 2015. The titular “angels” are human entities from a universe 1000 years in the future, who have learnt to draw from “all kinds of consciousness; ancestral, bodily, extraterrestrial, as well as animal, nature, cellular, and the cosmos.”[13] In so doing, they create a world that defies our current political, social and economic systems. Their game becomes a site of envisioning a radically different world.

In Morphogenic Angels: Chapter 2 – Alchemy of Perspectives, commissioned for the MUNCH Triennale, Keiken introduce a new character called Monkey Rabbit. Its development is based on a number of mediated conversations and workshops with deaf-blind Japanese artist, Sakura Sky (Hayato Tabata). Exploring how one might build and navigate a world in which one cannot be seen or heard, this edition of Morphogenic Angels attends to a group that tend to be overlooked by mainstream gaming initiatives, which subscribe to the continued primacy of vision. The work is shown in a dedicated space, the MUNCH Lab, on the sixth floor of the museum, which in the words of the artists “invites players into a layered sensory experience where transformation begins with how we choose to see – and be seen.”[14]

A concern for that or those who have been othered by dominant social, economic and political forces runs through many of the practices included in the MUNCH Triennale. This dovetails with my own queer curatorial approach and characterises both editions of the Triennale to date. Together, the artists in Almost Unreal propose alternate and more equitable realities in a multitude of different forms. The past – real or imagined – is mindfully mined. Even the most speculative and constructed worlds retain a physical presence, often through dance-like movements of their protagonists, whether animal, human, machine or hybrid. Two-dimensional scenes on screens spill out to envelop and engage the bodies of visitors in the space. The scale ranges from tiny dancers to giant eyes. Imagery is both handmade and computer-generated. In the slippages between the real and the unreal Almost Unreal is an invitation to imagine differently.

[1] The way I define “queer” is not limited to issues of sexual orientation, but rather refers to a critique or rupture of an existing order that is not only heteronormative but misogynist, white, anthropocentric, traditional in its values, conservative in its approach to artistic disciplines and disciplining. In short, a queer approach entails considering the other – the alternative that has been othered – by the dominant social order. Tominga O’Donnell, ‘The Machine is Us’ (2022) Avilable at: https://www.munch.no/en/exhibitions/archive/2022/the-machine-is-us/the-machine-is-us/

[2] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Future’, Holberg Prize lecture. Available at https://www.youtube.com/live/N4SdCezYZd0 [last accessed 6 August 2025]

[3] Marie Fredriksson in Don't Bore Us, Get to the Chorus (liner notes). Sweden: EMI Records, 1995.

[4] Karl Ove Knausgaard, ‘Tallenes tale’, essay in Klassekampen, 5 July 2025. Translated by Tominga O’Donnell.

[5] Michael Talbot, The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality (Harper Perennial, 1992).

[6] Philosopher Nick Bostrom was the first to propose simulation theory in the early 2000s with the paper ‘Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?’ published in Philosophical Quarterly (2003) Vol. 53, No. 211, pp. 243–255.

[7] The Computable and the Uncomputable Keynote Lecture by Alexander R. Galloway

Oct 9, 2020. https://veralistcenter.org/events/the-computable-and-the-uncomputable-keynote-lecture-by-alexander-r-galloway

[8] Debois Buhl, Nanna. 2023. Picture the Sky: Cosmic Code, Images, and Imaginaries. PhD dissertation. p. 98.

[9] Charlotte Johannesson in an interview with Rhea Dall in Charlotte Johannesson: Take me to Another World, p. 100.

[10] Debois Buhl, Nanna. 2023. Picture the Sky: Cosmic Code, Images, and Imaginaries. PhD dissertation. p. 60

[11] Johannesson hung out with the Sex Postols on their Scandinavian Tour in the summer of 1977. Lars Bang Larsen, ‘Charlotte Johannesson’s cyberfeminist textilepunk and its countercultural connections’ in Charlotte Johannesson: Take me to Another World, ex. cat. (Madrid: Museo Reina Sofia, 2021), p. 15.

[12] Malidoma Patrice Somé, Ritual: Power, Healing and Community (1993)

[13] https://keiken.cloud/work/morphogenic-angels-chapter-1/

[14] Part of the use of the MUNCH Lab involves workshops with the artists and Diamanten school for deaf-blind students, organised by exhibition mediatior Zeenat Amiri Waaler, Julie Parisi and the MUNCH Lab team.