Curator’s essay: Lawrence Abu Hamdan

In this essay, curator Tominga O’Donnell describes the backdrop to Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s exhibition Zifzafa at MUNCH, touching on exploitation in the Golan Heights in the name of green energy, imaginaries of sound, and practices of resistance.

I first met Lawrence Abu Hamdan (b. 1985) when he received the Edvard Munch Art Award in Oslo in February 2020.[1] It was pre-Covid and before the new MUNCH had opened. We walked around the raw concrete shell of the museum’s tenth floor gallery in hard hats as Lawrence tested the room’s acoustics. I was familiar with his practice from works like Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley (2013), a video showing the practice of people coming to the 1967 border between Syria and Israeli-occupied territories in the Golan Heights to shout to their friends and family across the so-called Purple Line. Among many subsequent works, the video and installation Rubber Coated Steel (2016) made a lasting impression. Through audio-ballistic analysis, it showed how two Palestinian teenagers in the West Bank had been killed by live ammunition rather than the rubber bullets the Israeli soldiers claimed they had used. Lawrence’s practice combines both investigative analyses used as “hard” evidence in court proceedings and art projects that speak to a more extensive range of emotion and imagination. He holds a PhD from Goldsmiths on the role of sound in legal investigations and has a long research practice in forensic audio analysis, whilst showing in some of contemporary art’s most hallowed settings.[2] His role has been summed up as a “private ear”. In 2023, he founded the London-based non-profit organisation Earshot, which produces audio investigations for human rights and environmental advocacy.[3]

Rubber Coated Steel, Exhibition view Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Aux frontières de l'audible Frac Franche-Comté 2023. Courtesy of the artist and mor charpentier Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Photo: Blaise Adilon

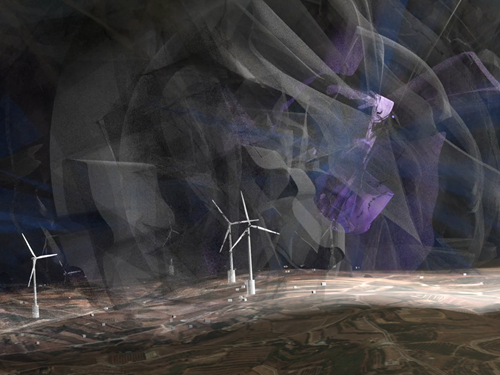

The Edvard Munch Art Award came with a cash prize and an exhibition at the new museum. One of the pleasures of working on these exhibitions is that they are remarkably open. They come with no requirement to show the work that led to the award or any other institutional requirements of fitting into a programme profile or servicing particular audience demographics. It is even untethered from the fervent artworld obsession with the new. It was, therefore, largely up to Lawrence what he wanted to show. When he suggested the then-ongoing investigation into planned wind turbines in the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights, and linked it to the Norwegian/Sámi context of wind turbine expansion here, I was immediately captured. We discussed this in London at the height of the 2024 protests in the Fosen Case against the wind turbines on Sámi land used for reindeer herding in contravention of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Together with indigenous opposition against mega wind parks in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico he noted new networks of solidarity form between those suffering under the architectures of “green colonialism” associated with wind power. Objections to wind turbines largely focus on two aspects: the visual – they are ugly and make a mess of the landscape under construction – and the sonic as they produce noise when the wind blows. Some also question their efficacy and their impact on the migration patterns of birds and other animals. Rather than being a simple protest against wind turbines, Lawrence’s exhibition at MUNCH touches on several salient questions around who is asked to make concessions to meet the targets set by international treaties to combat climate change; what impact renewable energy sources actually have and whom they benefit; and the role of noise in our immediate environments and imaginaries.

The backdrop to the exhibition that became Zifzafa at MUNCH was a request made to Earshot in 2023 by Al Marsad, the Arab human rights centre in the Jawlan, the Syrian Golan Heights, to develop a simulation of the impact the 31 planned wind turbines would have. The simulation was to be submitted as evidence in the court case Al Marsad was bringing against the Israeli company, Energix Renewables. In order to create the simulation of the planned wind turbines in the Jawlan, which were over 250 meters high, sound engineer Adam Laschinger went to Gailsdorf in Germany on behalf of Earshot to record the sounds of wind turbines of comparable size to those planned in the Jawlan. As Earshot write on their website: “The recordings and measurements taken in Germany made it possible to digitally convolve the noise of the wind turbines onto the topography of the Jawlan. The research and simulation of the planned wind turbines in the Jawlan has been used in a number of different ways, including for the art project, Zifzafa.[4]

“Zifzafa” is an old Arabic word that refers to a kind of wind that shakes and rattles everything in its path. It is the wind that brought volcanic soil to the Jawlan over thousands of years, making the earth especially fertile for growing vegetables, apples and cherries. The wind conditions meant that there was, in fact, a local energy initiative in development in northern Jawlan, which Energix initially tried to buy out, as a report from Al Marsad reveals.[5] After the local initiative was stalled by the Israeli army, the way was paved for Energix to move in. In a classic case of colonial extractionism, the state-owned and controlled energy-provider the Israeli Electric Company would be the sole customer of Energix’s proposed energy gains.[6] This follows a longer history of Israel exploiting the Jawlan’s natural resources, which supply a third of Israel’s water consumption.[7] What is novel, as such, about the Energix project is that it is planned for the five percent of remaining indigenous land. The sonic footprint of the wind turbines will render a much larger area unliveable.

When you work on a project for any length of time, names, key events and figures become second-nature, so allow me to zoom out for a moment to provide some contextual information: The Golan Heights in Syria were occupied by Israel in June 1967 during the so-called Six Day War. Of over 100 Syrian villages with over 100.000 people, only four, mainly Druze, villages and about 7000 people remained. The rest had been forcibly removed and prevented from returning. The term “Jawlan” was one of the ancient names for the area, which was revived by the occupying Israeli authorities in 1967. It has since been coopted or appropriated by the people of the Jawlan – the Jawlanis – as a distinct identity.[8] The “occupied Syrian Golan Heights” is the term used by the United Nations. Two thirds of the Golan Heights were occupied by Israel in 1967, and further territory was gained after the 1973 Yom Kippur War through a disengagement treaty between Israel and Syria. A United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) was charged with maintaning a buffer zone between the two countries along the so-called Purple Line from 1967.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, stillbilde fra Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley, 2013. Courtsey of the artist.

In his essay in the edited volume The Untold Story of the Golan Heights (2023), Michael Mason draws on Jürgen Habermas’s term “lifeworld colonization” to describe how Israel has gradually moved from a military occupation in 1967 to de facto annexation, “switching the occupation from military to civil government” by the 1980s.[9] Under the Golan Heights Law of 1981, Israel unilaterally imposed their jurisdiction and administration onto the territory in contravention of international law.[10] Since then, “Israelification” has meant that key public services, including water, energy supplies, education, emergency services and culture have been under Israeli control. The expansion of settlements, populated by Israelis has increased. Since 1981, Jawlanis have been offered Israeli citizenship. Those who have refused, have “undefined nationality” in the identity cards, effectively rendering them stateless. As Mason argues, “Jawlani identity is a dynamic hybrid of placemaking, Syrian nationality, the Druze faith and secular political ideas.”[11] The first municipal elections held in the Jawlani towns of Majdal Shams, Buq'ata, Mas'ade, and Ein Qiniyye in 2018 were largely boycotted as voter turnout was just over 1%. In 2019, during Donald Trump’s first presidential period, the US recognized the occupied territories as Israeli. After the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, Israel invaded the buffer zone and assumed control of the remaining 1/3 of the Golan Heights.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

The installation at MUNCH, in the museum’s characteristic tenth floor gallery in the “tilt” of the building consists of three parts. The video Zifzafa: Livestream Audio Essay (2025) is projected onto the whole of the slanting wall of the museum with the help of four projectors, thereby looming over visitors as they sit and watch a play-through the video game. Subtitles feature like the live chat sections on streamed video game play-throughs. This set-up evokes the recent tendency among some of the more famous gamers to also function as alternative news broadcasters. In a media landscape that is increasingly fractured and partisan, gamers who combine playthrough with “chatting” reach audiences that traditional news outlets rarely do via Twitch where they have millions of followers. A streamer like Turkish-American Hasan Piker has become a renowned for his combination of gaming, social and political commentary and the occasional ban from streaming platforms.

Still from Zifzafa computer game, courtesy of the artist and Earshot.

For Zifzafa, Earshot worked with Jawlani composer and sound artist Busher Kanj Abu Saleh for over a year on gathering field recordings from the area denoted as a wind park. These recordings were geo-located so that one can move through the terrain and listen to the sounds in each location, in addition to the simulated impact of the wind turbines. The 45-minute chat monologue in Zifzafa first introduces wind turbines as a form of branding for a serene future built on renewable energy against the silent backdrop of the simulated landscape of the Jawlan. As the turbines start up, Lawrence swiftly moves on to a series of similes of what 70–90 decibels will actually sound like, including “drilling through a dry wall” and “having a truck pass over your head”. The player moves through the landscape narrating the history of the Jawlan, entering a kookh (a small house or shed) and dwelling on some of the sounds Abu Saleh has collected, including a song by local vet Hassan Safadi and legendary flautist and shepherd, Ibrahim Zen. The song, the building of kookh’s, the establishment of autonomous water infrastructure, the growing of trees rather than vegetable crops are all acts of resistance by the indigenous Jawlanis. The narrative culminates in the story in Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote, where the titular hero charges at a “thirty or forty windmills all together on the plain”, thinking they are giants who are goading him.[12] It has given rise to the English idiom “tilting at windmills” meaning to fight enemies who do not really exist.[13] The adjective “quixotic” derives from the same book, meaning to be idealistic to the point of being unrealistic. Indeed, the narrator asks whether the Jawlani are being quixotic in their resistance to the Energix project. However, he retains an air of defiance, noting that even after laying injured on the ground Don Quixote vows that he will one day vanquish his enemy in the form of giant windmills. Picking up this reference, the wall to the left of the giant video game play-through features three screens. Tilting at windmills i, ii & iii (2024) are short CGI animations of six seconds that visualize the impact the sound of the wind turbines will make on the surrounding landscape.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

Opposite the tilted wall is a single-channel video projection Wind Ensemble (2024). It shows one of the small houses, which will find itself less than 50 meters away from a wind turbine. From the balcony of one of these houses, Jawlani musician Amr Mdah emerges to play his own composition on the saxophone. This becomes a defiant act of sonic resistance with links to the earlier work Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley. Along with Abu Saleh’s recordings of the flute and song, Mdah’s music becomes a celebration of indigenous Jawlani culture.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

Awareness of noise pollution seems to be on the rise. My Instagram feed is full of adverts for Loop Earplugs which encourage me to “take back control” over noisy environments. My phone sends me unsolicited “health data” on how loud my headphones have been playing. Spotify offers playlists of noises to block other noises. Audio disturbance is increasingly in the public imaginary, but what does it look like? In her book Atmospheric Noise, Marina Peterson describes how the metrics of noise – measured in decibels against different charts of recommended exposure – shifts away from actual experience, rendering the sensory as abstraction.[14] Tilting at windmills is an attempt to make noise visual and evoke Lawrence’s earlier works such as Air conditioning (2022). This installation of “sonic images”, which I saw at the Berlin Biennale in 2022, showed the “atmospheric violence” that Israeli fighter jets, UAVs and drones have caused to Lebanese airspace since 2006. The visual representation is based on extensive data gathering and analysis over many years, which is presented on a computer in the space, alongside the line of visual images that run the length of the gallery.[15] The dark plumes on a pristine blue sky vary with the duration of the noise and show the extent of aural pollution in Lebanon, in addition to the actual fumes emitted into the atmosphere. We need these visualisations in order to begin to fathom the role of sound in contexts like these. What Zifzafa does effectively is to combine the imaginary, the aural and the visual, enabling one to tog back and forth between the sonic landscape before the wind turbines and their potential impact on their surroundings. Through Abu Saleh’s field recordings, the project has also become an audio archive of the sounds of the local community – from children playing, bees humming and birds chirping to the sound of farming tools, water pumps and a boom box. The giant blades of the wind turbines will not just be cutting through air but will be severing ties between people and the landscape, and each other.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, The Sonic Image. Installation image Sharjah Art Foundation 2022.

One section of the narrative in Zifzafa describes a paradoxical story from Jawlani artist and activist Wael Tarabieh. In the protests against the wind turbines, the Jawlanis were joined by members of an Israeli environmental charity. Their motivation was preserving the “empty” and natural calm of the Jawlan. This notion of “emptiness” is something that ties the various territories earmarked for the development of renewable energy together. Whether it is reindeer pastures in Norway/Sápmi or indigenous lands in Oaxaca, Mexico or the last native lands in the Jawlan, they are all considered terra nullius, that is devoid of any existing human or non-human rights to them. They are the focus of “aeolian extractivism” whose exploitation does not benefit local communities but international investors or state governments who traditionally have not served these communities well at all.[16]

The driver behind this use of renewable energy is the international climate treaties that countries have signed up to – from the Kyoto Protocol (1997) to the Paris Agreement (2015). Whilst the devastating effects of climate change makes it imperative that something is done, it is telling that many of the communities that are being asked to make concessions in order for nation states to meet their climate commitments are often those who have been marginalised for decades. Moreover, these communities are often not the ones who have contributed most to the escalating climate crisis. Giant wind parks are a strong symbol of environmental action being taken. However, they are not a comprehensive solution. If the Energix wind turbines would be built in the Jawlan, they would only produce 0.6 per cent of Israel's energy need.[17] The project would, however, cover over 20 percent of Israel’s renewable wind energy goals on its own.[18] This points to the major discrepancies between the goals of climate change action and the actual energy requirements of countries. It also begs the question of whether environmental concerns have become a front for (further/re-) colonising of land in the Jawlan.

“Comparisons are…always odious”, Cervantes wrote in a well-known quote from Don Quixote.[19] The territories in Sápmi, the Jawlan and Oaxaca are vastly different contexts, and comparisons may be inappropriate, if not “odious”. However, they are part of new networks of solidarity for those suffering under the aeolian exploitation associated with the green movement. Against large multi-national companies and nation states with little regard for international law protesting may seem futile. However, is not quixotic to say that resistance in one place can allow hope to be carried on the winds to another.

[1] https://www.munch.no/en/edvard-munch-art-award/lawrence-abu-hamdan-er-prismottaker-av-edvard-munch-art-award-2019/ The award has since been replaced by the MUNCH Award, which honours artistic freedom of expression: https://www.munch.no/en/munch-award/.

[2] See his website for a list of museums, galleries, biennials and awards http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/information

[3] Earshot projects include audio enhancement and speech analysis in the case of the French police killing of teenager Nahel Merzouk in Nanterre; audio and debris analysis of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in airstrikes on journalists in South Lebanon; and acoustic surveys of Saydnaya, the Assad regime’s torture prison in Syria. https://earshot.ngo/ for an overview of their all their investigations [last accessed on 3 August 2025]

[4] The material is yet to be submitted in court proceedings but has been used widely for advocacy and public information purposes, including a BBC Arabic documentary. Zifzafa as an art project has taken different forms including live performance, video games and gallery installations. In addition to MUNCH, the project has been supported by Barakat Contemporary, Alserkal Arts Foundation, Festival d'Automne à Paris, CENTQUATRE-PARIS and L'Art Rue as part of Dream City 2025.

[5] Aaron Southlea and Dr Nazeh Brik, WINDFALL - The exploitation of wind energy in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights (2019) https://golan-marsad.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Windfall-–-The-Exploitation-of-Wind-Energy-in-the-Occupied-Syrian-Golan.pdf (last accessed 2 August 2025), p. 17.

[6] Ibid p. 12.

[7] K. Kathy, ‘Water is Life: The Legality and Consequences of Israeli Exploitation of the Water Resources of the Occupied Syrian Golan’ in Forgotten Occupation – Life in the Syrian Golan after 50 Year of Israeli Occupation, Al-Marsad – Arab Human Rights Centre in Golan Heights (2018), p. 119.

[8] Munir Fakher Eldin, ‘Power, Politics and Community: Resistance Dynamics in the Occupied Golan’ in Journal of Palestine Studies, 49 (1), 2019.

[9] Michael Mason, ‘The Politics of Lifeworld Colonization the Occupied Golan’ in Dajani, Fakher Eldin & Mason (eds), The Untold Story of the Golan Heights – Occupation, Colonisation and Jawlani Resistance (I.B. Taurus, 2023), p. 23.

[10] The UN Security Council Resolution 497 declared the Israeli Golan Heights Law “null and void and without international legal effect” on 17 December 1981.

[11] Mason, ibid. P. 40.

[12] Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, trans. Tobias Smollett (Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1998), p. 44.

[13] Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus, Cambridge University Press.

[14] Marina Peterson, Atmospheric Noise – the indefinite urbanism of Los Angeles (Duke University Press, 2021), p. 16.

[15] Lawrence also presents this "violation data" on the website airpressure.info so that it is publicly accessible beyond the walls of the exhibition space.

[16] Howe, C., & Boyer, D. (2016). Aeolian Extractivism and Community Wind in Southern Mexico. Public Culture, 28(2 79), 215–235. http://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-3427427

[17] Quoted on the Earshot website: https://earshot.ngo/investigations/zifzafa (last accessed 14 July 2025).

[18] WINDFALL, ibid. p. 26

[19] Cervantes, ibid. p. 462.