Critical Impulses: New Snow 1

MUNCH invited young writers from the journal Paragone to engage in critical reflection on the New Snow 1 project.

Today’s young people are not the first generation to face the world with a thousand questions. Neither are we the first generation seeking answers to these questions in the prevailing visual culture. We are, however, the first generation who, via reverse image search and similar AI-based algorithms, can actually ask questions using images. Google Lens and Pinterest Lens are both examples of image recognition technology which we use all the time, either to find the original version of a meme, or to find out the title of an unidentified artwork. By uploading images, or simply pointing our cameras at an object we want to learn more about, we are using these technologies to carry out a visual analysis which bears fruit in the form of similar images, with information attached. A similar technology is used in New Snow, an interactive experience running in the MUNCH Lab.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

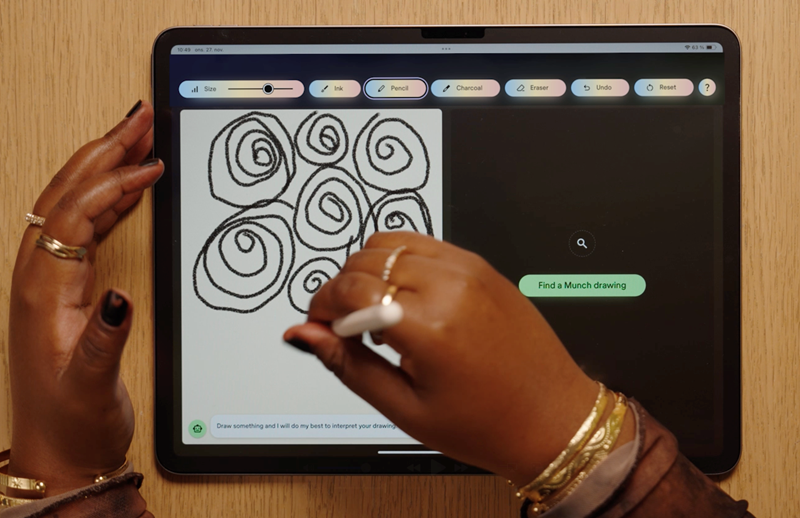

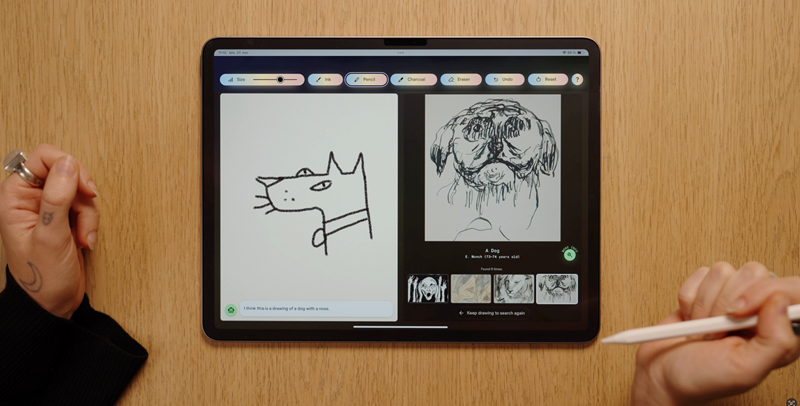

With the help of AI models developed with an external technology partner, visitors can use their own drawings to search through the archive of Edvard Munch’s works on paper. This means that a brief sketch on one of the tablets in the room is a substitute for a linguistically formulated prompt. Instead of searching for the word ‘flower’, you can draw a flower as best you can, and wait for the AI model to interpret what you have drawn, before combing through the archive for similar motifs.

Researching the possibilities of ‘formulating’ a visual search, therefore, is an exciting aspect of this interpretative process, which is already familiar from the tools we use on a daily basis. All the same, New Snow is powered by two small open source AI models, unlike the more all-encompassing image search functions we know from the above-mentioned platforms. MUNCH does not save any of the drawings, nor does it use them to train its AI. Some of the unease we associate with headlines about AI models which hoover up and steal pretty much all of the visual material they come across, is therefore kept away from the Lab and the drawings made within it. Art can afford to be ambivalent, even mysterious, but artificial intelligence cannot. On MUNCH’s website you can find several articles which try to explain the technology and research behind New Snow. In fact the Lab where New Snow is installed was constructed precisely for this purpose. Instead of rolling out ‘finished’ innovations directly into exhibitions, they give visitors hands-on access to projects which are still in development.

There seems to be two ways to use New Snow’s AI. You can either use it as a search engine, which shows you drawings resembling a motif you are looking for, or as a kind of randomiser, which shows you slightly randomly chosen drawings based on your own slightly random drawing. You can be both playing and searching while exploring the archive. At the same time, a constantly updating screen keeps count of your searches and finds, which gives you the vague feeling of a ’search race’ against other users in the room. It’s a little hard to understand if this is meant to inform or entertain, especially when the whole room is lighting up with various flashing bulbs every time a new drawing is retrieved from the archive. This type of sensorial stimulus as a ‘reward’ for completing a task is a little reminiscent of the many kinds of sound, light and vibrations which different apps use to trigger dopamine production in younger users. In this way it is not only play and curiosity which are being implemented in the Lab, but also a form of gamification – the integration of gaming elements in non-gaming situations.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

A large proportion of the platforms we use today are shot through with cynical gamification strategies. This integration of gaming elements in non-gaming situations somewhat detracts from the Lab’s integrity in presenting MUNCH’s experimental technology. The Lab’s identity and project sets itself apart from other platforms we see every day. You won’t necessarily get a job through LinkedIn (‘You’ve made it! Your profile is 46 times more likely to be found in recruiter searches!’), and you won’t necessarily learn a whole new language in Duolingo (‘Don’t let your streak die – just do 5 minutes today!’). These are games – star ratings, notifications and semi-promotions. The potential – directly or indirectly – to reposition the actual art experience as a kind of game, therefore, appears extremely alarming. But perhaps this is because we have seen it being developed in the wrong hands, and by people who want two things: money and attention. And not even in the name of art! Sigh.

And here we should be asking the question: why? So people don’t get bored at a museum? Transferring the logic of social media to a museum because people like social media? To ‘effectivise’ art experiences? At first sight, a room with ten teenagers sitting with individual iPads giggling at the AI’s misinterpretations doesn’t exactly seem like a great leap forward for art. On a second look, neither does it seem like a great leap forward for technology. On a third look, after adjusting your glasses and taking a moment to consider, it does in fact start to look like a genuine alternative: a step that doesn’t try to go too far forward at all. Sandwiched between the museum’s other exhibitions, New Snow is more of a playful sideshow where existing technology and art can be used without having an absolute goal in mind.

With that said, playful sideshows can quickly become dizzying in a museum which is already saturated with bright colours and a steady stream of visitors. One concern that crops up at the sight of New Snow’s glowing screens and flashing lights is whether it might in fact be a little overstimulating. In addition, the tailored presentation means that everyone is left with a unique set of impressions that are not shared by the museum's other visitors. People may fall silent over their coffee cups in the Skybar if everyone has left the same room with a different impression. To people like us – young people interested in art – it may seem that an innovation with similar principles to gaming and marketing lies behind a fairly superficial, individual and supremely stimulating art experience – since this is what we experience on a daily basis. At a time when everything seems to be a constant battle to resist the brain rot of media consumption, it’s sometimes nice just to let the art be the main focus of a museum visit, instead of playing charades with an iPad.

‘The camera cannot compete with the brush and palette, as long as it cannot be used in heaven or hell,’ wrote Edvard Munch in a 1929 note. This can be interpreted to mean that human insight into dreams and fantasies of the hereafter can never be recreated in a photograph. Today you could argue that this is no longer correct, since experimental photography can show much more than documentary depictions. Nevertheless, the argument recalls the criticism frequently levelled at AI. Criticised for having no soul, feelings or cultural understanding, AI is often portrayed as a cold, mechanical entity which threatens to drain all human essence from the art we surround ourselves with. In New Snow, for example, you can see AI playing the role of a kind of interpreter, a task previously reserved for people with some degree of competence in the subject. This is clearly not good news for us: art students hoping to work as exactly this kind of bridge between art and the people. It is, however, interesting to see how this use of AI as a medium permits a more open and unbiased selection process in terms of what gets put on view to the museum’s public.

The opportunities for opening up, in this case Munch’s sketches and fragile works, make the integration of new technology an inevitable aspect of the art institutions of the future. At the same time, AI is often associated with problems concerning the human, emotional dimension in art. This particular dimension does not necessarily have to strive for innovation or surface user-friendliness. Like photography, AI is one more bit of technological progress making many tasks more effective. OK, so some portrait painters lost their income to a camera, but by and large painting as an art form survived. Perhaps the same will apply to AI? Certain projects, like New Snow’s ambition to give access to an archive of 7000 drawings, would simply not have been possible without the use of some form of artificial intelligence. Whether or not AI can dream of heaven and hell, it is a useful tool for communicating everything in between – in other words, all forms of expression which already exist, in the world’s infinite archives.

Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

Like any other tool, artificial intelligence can be used for good or evil. And as with any other tool, the argument is also used that progress, development and innovation are inherently good qualities. Young people are often portrayed as the prevailing forces driving these developments. An unfortunate consequence of this is that special features aimed at young people have a growing tendency to share similarities with museums of technology. Sometimes it can actually be quite stressful to feel that you yourself are the reason why society is aligning itself with our poor, dopamine-addled brains. Maybe we would have benefitted from having a grown-up in the room, who could set the parameters for a more calming experience – an intelligent artist, rather than an artificial intelligence?