Accessibility in Lifeblood

EXHIBITION

Floor 3

27.06.–21.09.2025

Welcome to Lifeblood – Edvard Munch. Here you will find information to support your visit to the exhibition. I think of curatorial work as care work, and I hope these materials provide you with what you need for a meaningful experience.

These pages are intended as an introduction to the exhibition for people with reduced mobility, visitors who are blind or have low vision, and visitors who are deaf or hard of hearing. You will find a map, accessible descriptions of room layouts, and descriptions of selected objects and artworks.

We welcome your feedback on accessibility measures so that we can improve such features in future exhibitions. You can send your feedback directly to the exhibition’s mediation developer: Nikita.mathias@munchmuseet.no (link to email).

-

The 3rd-floor exhibition space has a ceiling height of 8 metres and a total floor area of 1095 square metres. The exhibition has eight themed rooms and follows a linear route. Each room is shaped differently. The rooms contain artworks, objects and documents on the walls and in glass display cases. There is also specially designed free-standing seating for the public. The exhibition spaces are lit with a comfortable, average strength lighting, and are designed with the needs of wheelchair users in mind, leaving enough space to turn. All the works are placed at heights suitable for viewing from a wheelchair.

Language and Text

Each room contains a text that explains the overall theme of the room. Additional texts are placed on the walls, as well as on or next to glass display cases, and sometimes on panels hanging on the side of the display cases, which can be lifted up and read separately. Each object and artwork is captioned with its title and other practical information. Explanatory texts are provided for many of these items. All texts are in both English and Norwegian.

Sound

In the rooms titled Sickness and Death, Wellness and Tourism, and Care, you can hear room-specific sound effects. Sickness and Death has an audio narrative about Edvard Munch’s motif The Sick Child, which you can hear on headphones installed in the seating. In Wellness and Tourism, you can hear an environmental soundscape; and you exit the exhibition to the sound of a heartbeat.

Exhibition Space and Lighting

The exhibition space is lit at a low and consistent light level to protect delicate works on paper. Slight increases in lighting are used to guide a natural flow through the rooms. The exhibition contains no flashing or strobe lights.

Seating

The exhibition space offers various different types of seating, including open benches, benches with arm rests and back supports, benches with vertical, high lumbar support, and benches with different ergonomic configurations giving visitors the option to sit or lie down.

-

At the entrance you turn left, through a narrow passageway leading into the exhibition. The walls in this passageway are painted black, the lighting is low.

Below you will find information about, and descriptions of, the various rooms in the exhibition, along with selected works and objects from each room.

-

Room description:

The first room in the exhibition is painted red, and you see a wall on which the exhibition title Lifeblood is displayed, lit from behind. From the right hand side of the wall, a curved, three metre long bench comes out at a right angle. Above the bench is an eight-metre long wall with paintings and a display case, each with its own text. On the right of the wall is the exhibition text for the whole room.

Introduction text:

Between Edvard Munch’s birth in 1863 and his death in 1944, modern medicine fundamentally changed people’s experiences of birth and death, sickness, care and healing. Lifeblood shows Munch’s art with medical objects from his lifetime, inviting you to explore his life and work in relation to changing practices of healthcare.

Munch called his art his ‘lifeblood’, a kind of medicine that could provide a ‘healthy release’ for both him and his public. Munch saw himself as a sick man as well as a healer. This self-image was deeply rooted in his personal experiences. Both he and his loved ones suffered at various times from chest diseases, mental distress and other afflictions. Among his family and his circle of friends and patrons, there were medical doctors, nurses and other caregivers.

This exhibition offers fresh perspectives on Edvard Munch’s life and art. You might also find yourself reflecting on how modern medicine continues to shape our lives.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: On the Operating Table, 1902–03

A man is lying diagonally on a hospital operating table with his head placed at the lower right of the canvas. Next to the man’s legs stands a female nurse holding a bowl of blood. There is also a patch of blood on the operating table. Behind the table, three doctors in white coats observe the scene from a corner of the room, while members of the public watch through a window.

Context: A Surgical Spectacle

September 1902: a doctor is called out to a cottage in the coastal village of Åsgårdstrand. Edvard Munch’s left hand is covered in blood – a bullet has struck the middle finger. The shot was fired – likely by Munch himself – during an argument with his lover, Tulla Larsen. The artist is transported back to Oslo for X-rays and surgery at Rikshospitalet, Norway’s national hospital. Soon afterwards, Munch begins painting On the Operating Table, a self-portrait inspired by this traumatic and painful event. In the painting Munch shows himself as a vulnerable patient, attended by faceless doctors, and observed by spectators. A deaconess nurse holds a bowl of the artist’s ‘lifeblood’. It spills onto the canvas, creating a strange and suggestive shape.

A Deaconess’s uniform, circa 1900

The uniform of a deaconess is displayed on a mannequin dummy. It consists of a white shirt with a collar under a long blue skirt with white spots. Above the skirt, a white apron with two large pockets is fastened across the chest with safety pins. White sleeves, fastened with buttons, hang from the skirt over the elbows. The mannequin also wears a pair of black tights.

A white nurse’s cap is held on the head with a chin strap. The cap was awarded at the end of a nurse’s training, marking the start of their full employment.

![Deaconess uniform on a mannequin: white shirt, blue spotted skirt, white apron, detachable sleeves, black tights, and a white nurse’s cap with chin strap. The cap symbolises the completion of training.]()

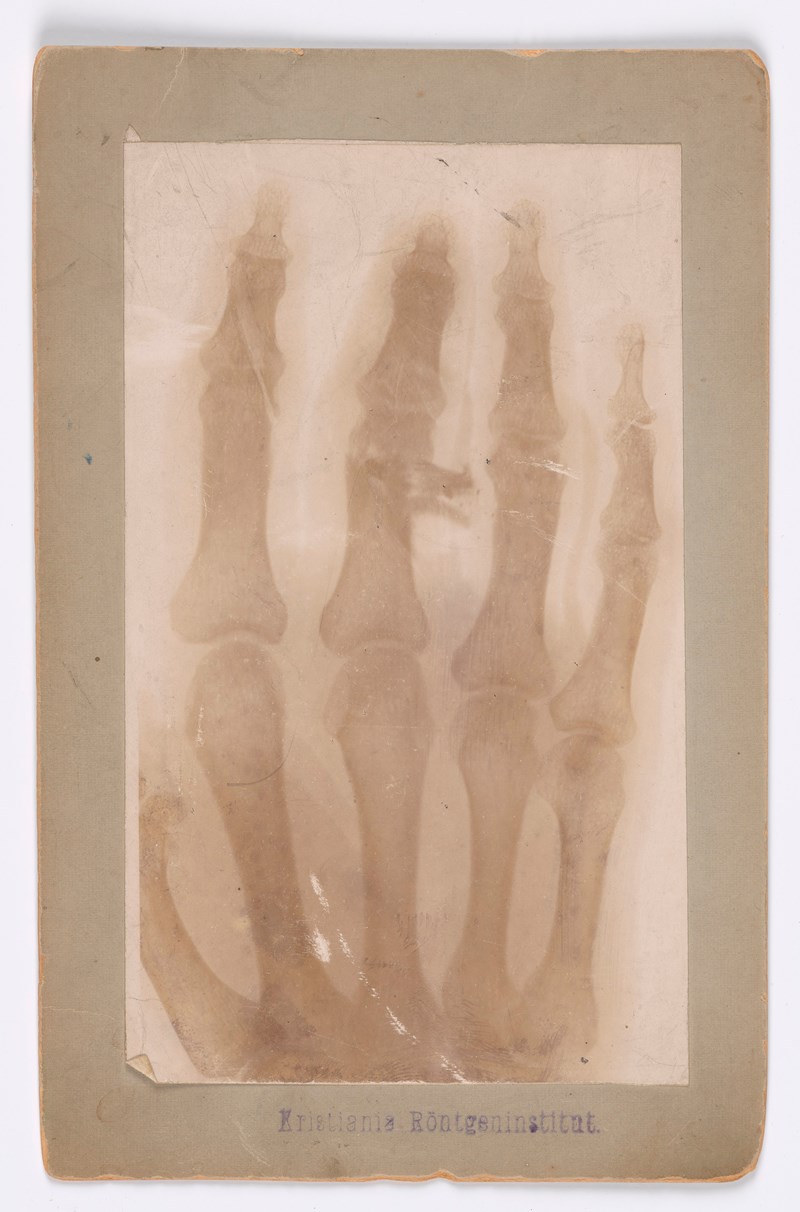

X-ray photograph of Edvard Munch's left hand, 1902

In September 1902, Edvard Munch’s left hand was x-rayed after he was shot in the middle finger. In this image we see the bones in Munch’s hand showing the injury to his finger.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Hospital Ward, 1902

We see a hospital ward with two rows of beds separated by a central walkway. In the beds on the left there are three patients, two of them sitting upright, with their necks bent backwards so that their faces point towards the ceiling. In the foreground, the third patient lies on their side, turned towards the viewer. In the background, standing in the walkway is a deaconess nurse looking at the empty beds on the right.

![]()

-

Room description:

This room is oblong and painted dark brown. In one corner is a chair from the Munch family home, on a plinth measuring 2.4 metres on each side. In this room there is a 2.7 metre curved bench, with arm rests and an integrated magazine rack. The room also contains a freestanding display case adapted for wheelchair users, with 75 cm between the floor and the case. At the end of the 16 metre long wall on the left, is the way out to the next room.

Room theme text:

‘Disease and Insanity and Death were the black Angels that stood by my cradle.’ – Edvard Munch

For Edvard Munch, modern medicine promised to hold back the ‘black angels’ of sickness and early death. Munch’s father, Christian, was a doctor. The artist’s brother also studied medicine but died of pneumonia shortly after he qualified.

The young Munch accompanied his father on house calls and observed him at work. He never took up his father’s profession, perhaps because his own poor health kept him out of school for long periods. However, he did study anatomy as part of his artistic training.

The Munch family letters and diaries are full of details about medical treatments, trips to pharmacies, childcare, and nutrition advice. These documents, together with many of Munch’s works, confirm that health issues and care preoccupied the family.

Painting by Edvard Munch: The Infirmary at Helgelandsmoen, 1884

The interior of a military hospital. Two beds are placed diagonally in the foreground. In the bed at bottom right, a young man is leaning in his bed with his leg stretched out in order to relieve his bandaged foot. Next to him in the other bed lies a man whose legs are under a blanket. A woman is sitting on his right. As she looks into his eyes her arm rests gently on his. A little girl stands just behind her.

![]()

Human Skeleton, 1885–1900

A human skeleton mounted on a plinth, previously used for anatomical study. The skeleton is loaned from the Norwegian Museum of Technology. A knowledge of anatomy was extremely important for both artists and doctors. The skeleton as a motif is often found in Munch’s artistry.

![A human skeleton mounted on a plinth, used for anatomical study. On loan from the Norwegian Museum of Technology. Reflects Munch’s interest in anatomy, a recurring motif in his work. The bones show signs of age, with some dark discolouring to the rib cage.]() The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, MunchmuseetA Wicker Chair from Edvard Munch’s family home, circa 1860

A wicker chair with a cushion decorated with a pattern of yellow flowers. This exact chair has been depicted in several of Edvard Munch’s works. Many members of his family, including Sofie Munch, Edvard’s sister, used to sit in this chair when they were ill.

![]()

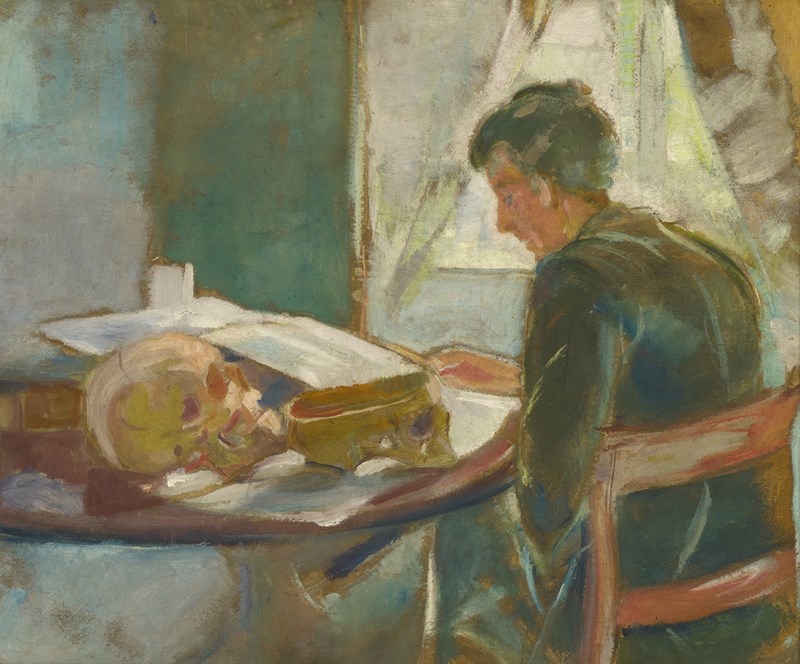

Painting by Edvard Munch: Andreas Munch Studying Anatomy, 1886

The artist’s brother Andreas Munch sits at a small round table, deep in his anatomy studies. On the table are two different skulls together with many papers. He sits by a window with white, see-through curtains that create a luminous atmosphere.

![Portrait of Andreas: On the right side of the painting, a man is seated at a table in front of a window, studying. On the table are two skulls, one whole, the other with its top half cut off.]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Karen Bjølstad after Bronchitis, 1888

As well as being Edvard Munch’s aunt and nanny, Karen Bjølstad was an artist. Here she appears pale while recovering from illness, looking away from the viewer with a distant gaze.

![]()

-

Room description:

This room, painted in green-brown shades, contains multiple versions of Edvard Munch’s well known motif, The Sick Child. A 2.8 metre long curved bench with a high backrest is placed in front of them. At one end of the bench, headphones are installed. Visitors can use these to listen to an audio narrative about The Sick Child. A display case extends from the back of the bench, adapted for wheelchair users, with 75 cm between floor and case. At each end of the display case there are text panels containing transcripts of letters between Edvard Munch’s parents. These can be picked up and held while reading. The information is provided in both Norwegian and English.

Room theme text:

Edvard Munch was deeply affected by the early deaths of his mother and sister from tuberculosis, and by his own experiences of chest disease. You can see this in some of his best-known motifs, including The Sick Child and Death in the Sickroom. Munch’s direct confrontation with sickness and death at an early age made him question whether his father’s medical skills and religious views were enough to protect their family.

Munch maintained close relationships with doctors throughout his life. This allowed the artist to enter the homes of people who were sick and to visit medical institutions as an observer. Here he could sketch and paint images of people waiting for treatment, doctors and nurses, and the grief and anguish of loved ones as they gathered around the death bed. These works remind us that sickness, disability and death are more universal experiences than health.

Painting by Edvard Munch: The Sick Child, 1885–86

A pale, sick young girl sits propped up in bed. Her face is painted in profile against a large white pillow. She has bright orange hair and a green top. A woman sits to the right of the bed, dressed in dark clothing and with her head bowed down as she holds the girl’s hand.

Context: Sick Children

The Sick Child is one of Edvard Munch’s most well-known motifs. He based it on his memories of his sister Sophie Munch, who died from tuberculosis at the age of 15. The actual model for the motif was a girl named Betzy Nilsen. He met her while accompanying his father on a house call. In different versions of The Sick Child, Munch suggests the many horrendous symptoms of tuberculosis: fever, pallor, weight loss and coughing up blood.

![The Sick Child: A red-haired girl sits upright in a chair propped up by a pillow and looking to the right. A woman appears on the right, head bent over.]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Death in the Sickroom, 1893

Grieving family members stand around in a lightly furnished room with a green wall and orange floor. In the foreground, a young girl with a red face and orange hair is seated in a chair with her back bent, her face turned away from the viewer. Behind her, a woman faces the viewer with a confrontational expression. Standing back-to-back with her is a man whose profile is turned away from the viewer. In the background on the right, a woman stands near a wicker chair with its back facing us. In front of the chair is an elderly man praying for the person sitting in the chair. To the far left in the background, another man leans his arm against the door frame.

![]()

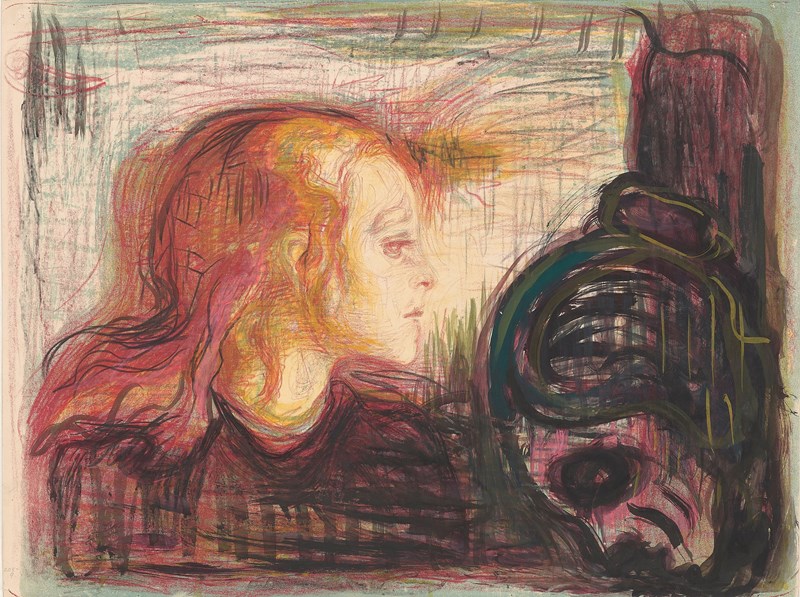

Colour lithograph by Edvard Munch: The Sick Child I, 1896

The sick child is seen at close range, focusing on the head of the young girl who is depicted in strong orange and yellow tones. Next to the child, a skeletal female face is printed in profile. The woman has dark, hollow eyes and deep wrinkles on her purple cheeks.

![]()

Blue Henry sputum bottle for tuberculosis, 1890–1920

A cobalt blue, egg-shaped bottle for tuberculosis sufferers to spit into. Its length is 11 cm. The lid and metal base are made of metal.

![A cobalt blue, egg-shaped bottle for tuberculosis sufferers to spit into. Its length is 11 cm. The lid and metal base are made of metal.]() The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

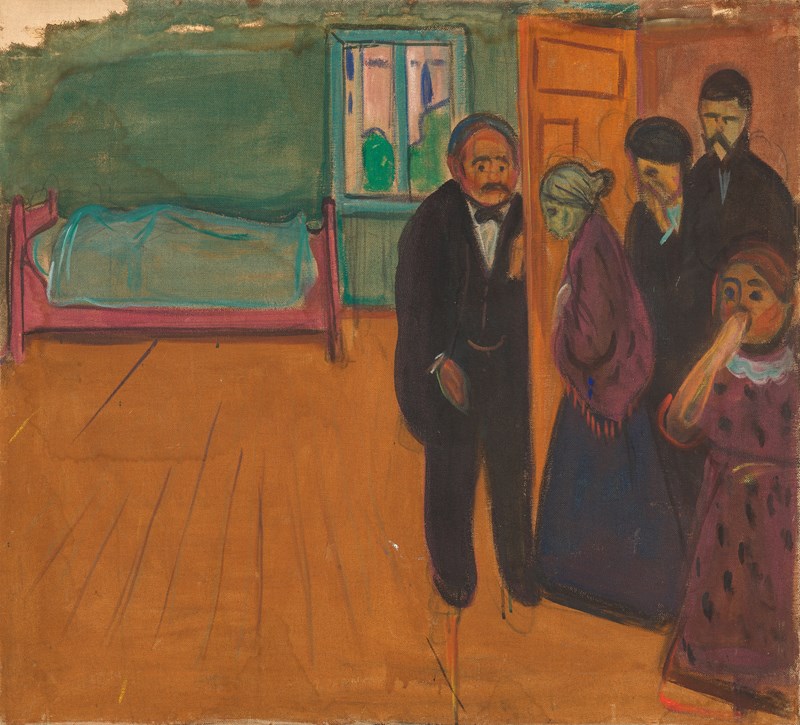

The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, MunchmuseetPainting by Edvard Munch: The Smell of Death, 1895

A sparsely furnished orange and green room with a single bed and a window in the background. Under the bedcover we see the shape of a human corpse. In the foreground to the right, a group of five people stands near the door. Their faces are green and grey and they wear dark clothes. The young girl closest to the foreground is holding her nose in disgust at the smell of the dead body in the room.

![]()

Sound:

The bench in this room features headphones with an audio narrative about Munch’s different versions of The Sick Child, available in Norwegian and English.

Read the script of the audio narrative here:

[Narrator:] The Sick Child

[Deep and reinforced sounds of scraping and scratching, atmospheric soundscape in the background building up?]

How can you express and make sense of painful, traumatic memories… like losing a sister for instance?

Edvard Munch found his own way of doing that.

The fabric of the canvas becomes a kind of wounded skin… [scraping and scratching sounds lingering in the background?] scarred with cuts and bruises.

Sophie Munch was 15 when she died from tuberculosis. Edvard – her younger brother – was 13 at the time.

What does an experience like this do to you – how does it affect you, on the surface and deeper inside?

Munch was in his early twenties when he made this painting. This was several years after Sophie’s death. Maybe that explains all the layers of paint, the scraped patches. As time passes, the memory of the sister he loved is fading away. Her last moments are becoming harder and harder to remember. [sounds of scraping and scratching swelling up again] The artist operated on the canvas, cutting it and scratching it, to try to restore his memory of her.

Perhaps that’s why he needed another sick girl, Betzy Nilssen, as a model for this painting. Because he could no longer fully visualise Sophie as a living person. The sick child is both Sophie – Munch’s fading memory of her – and Betzy. Most of all, the Sick Child is a scar that never fades. Can you feel it?

-

Room description:

This room has light blue walls and a 2.7 metre curved bench with an armrest and integrated magazine rack. The bench extends into a tabletop where a loom is placed as a tactile part of the display. The room also contains a freestanding display case adapted for wheelchair users, with 75 cm between floor and case.

Room theme text:

Edvard Munch believed that he and his siblings had inherited their father’s melancholy and nervous nature. In Munch’s art, women and men experience melancholy, which we might now call depression or low mood, in different ways. Melancholic (and ‘hysteric’) women are often shown in institutions, as figures of pity and sympathy. Melancholic men, on the other hand, often appear in contemplative states of mind associated with artistic genius.

This gender divide reflected and reinforced prejudices in wider society. People who didn’t conform could be sent to an asylum and mistreated. Others, however, spoke of finding refuge in asylums. Laura Munch, the artist’s sister, was in and out of psychiatric institutions for much of her adult life.

Edvard Munch met several psychiatrists in Paris during the 1890s. Some of them collected art made by their patients. They gave Munch access to hospitals, allowing him to develop an artistic language of mental distress. He showed people’s emotional suffering with both curiosity and empathy.

Painting by Edvard Munch: Women in Hospital, 1897

Four women in an empty room with a simple blue wall in the background. The woman nearest the foreground is completely nude and is seen in profile walking towards the left. Behind her are two half-naked women looking away from the viewer. Finally, there is a half-naked woman standing with her back to the painting’s right-hand edge.

![Women the Hospital: A naked older woman stands in the foreground of the painting, facing to the left. Three other women, one seated, appear in the blue and brown background, wearing only black skirts, their chests unclothed.]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Melancholy, 1900–01

A woman in dark clothing is sitting in the middle of an orange-coloured room. In the foreground, next to the woman, there is a round red table decorated with a flower in a pot. Behind the woman is an open window with a view of the sea.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Inheritance, 1897–99

A red-faced woman holds a handkerchief to her mouth. She sits upright on a bench and looks down at her thin, naked infant. The baby is lying on a white blanket, with its entire body exposed to the viewer. Red spots are visible on the baby's chest.

![]()

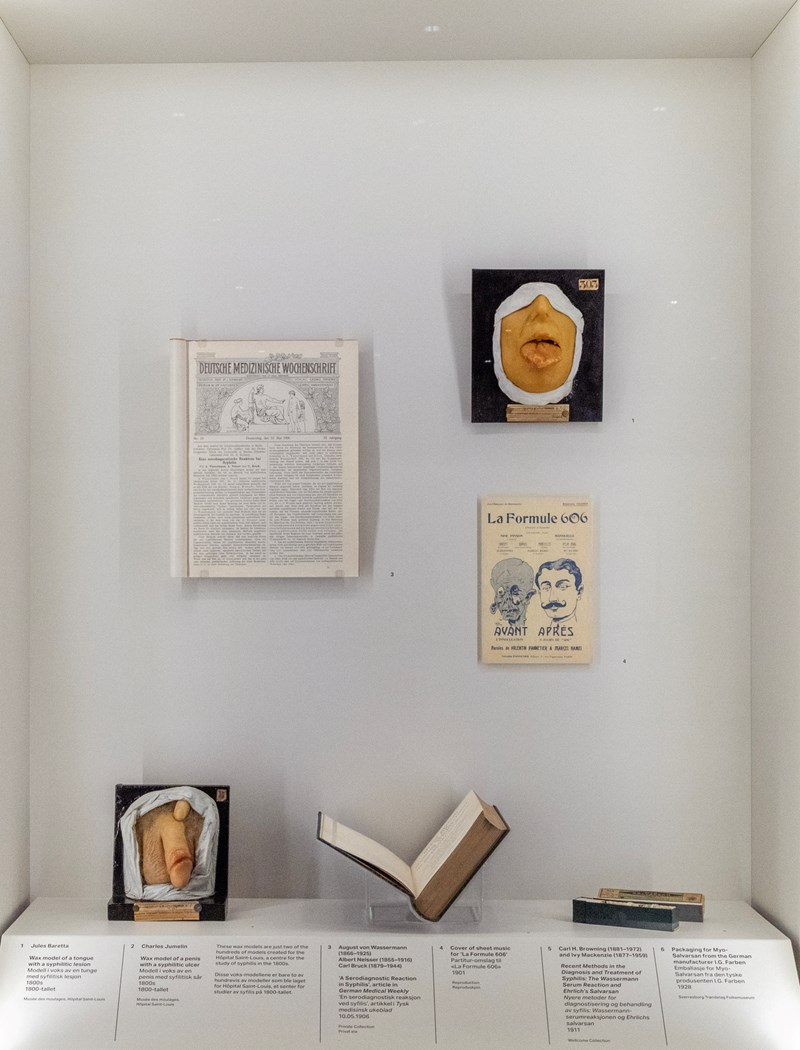

Wax model of a tongue with a syphilitic lesion, made by Jules Baretta, 1800s

A lifelike anatomical model of the lower part of a face, from the Saint Louis Hospital in Paris. The tongue is sticking out of the mouth. On the tongue you can see sores that are symptoms of syphilis.

![A lifelike anatomical model of the lower part of a face. The tongue is sticking out of the mouth. On the tongue you can see sores that are symptoms of syphilis.]() Musée des Moulages, Hôpital Saint-Louis, AP-HP. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

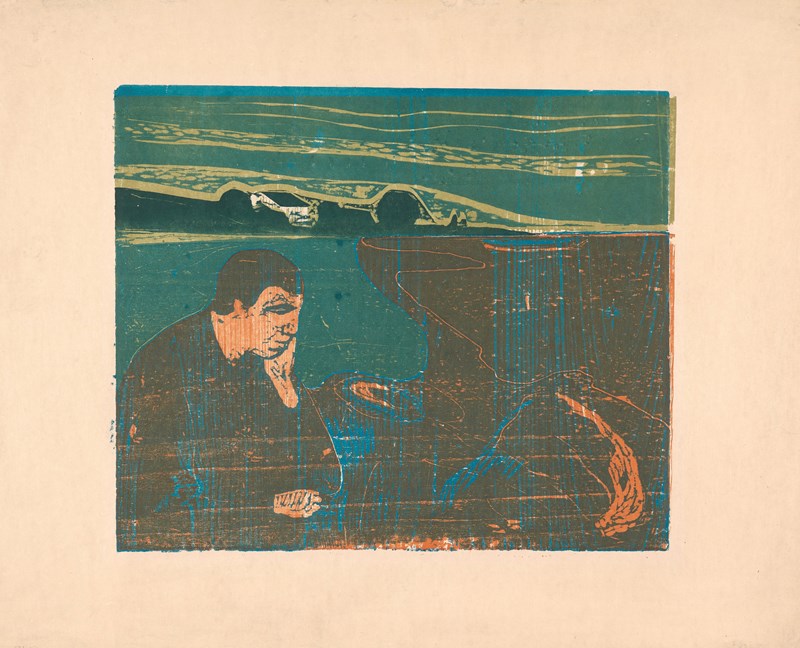

Musée des Moulages, Hôpital Saint-Louis, AP-HP. Photo: Ove Kvavik, MunchmuseetWoodcut by Edvard Munch: Evening. Melancholy I, 1896

A man sits on some rocks on the seashore, facing right in profile. He sits with his back hunched, his chin cradled in his left hand. In the background is the sea, rocks, mountains and a white house.

![]()

-

Room description:

This space is painted in a light blue-grey colour. Next to the entrance on the right, an antique incubator stands on a low (20 cm high) platform. Next to this is a curved bench, with no armrests or backrest, 1.15 metres long. In the centre of the room, there are two curving exhibition stands facing each other, which are adapted for wheelchair users. At the end of the display stand is a curved bench measuring 1.91 metres. To the left of the entrance, there is a display stand 1.3 metres tall.

Room theme text:

Edvard Munch lived in an age of rapid technological development. The growth of shipping and rail networks enabled him to travel all over Europe to build his reputation as an artist. But it also allowed diseases like tuberculosis and influenza to spread further and faster than ever before.

Technologies such as X-ray photography and powerful microscopes allowed people to view bodies in new ways, even down to single cells. Munch was fascinated by X-ray and microscopic images. If he had lived a little longer, he would no doubt have been excited by today’s imaging technologies such as ultrasound and MRI.

As a young man, Munch belonged to the Kristiania Bohemia, a group of artists and writers in Oslo who promoted free love. Movements like these were aided by modern contraceptive technology, which promised to give people more freedom over their sexual health and reproduction. But birth control was also used by the eugenics movement as a political tool to limit ‘unwanted’ population growth.

Incubator, circa 1890

An incubator made of dark stained wood is mounted on a stand of black stained wood carved with decorative waves. The lid has a built-in glass plate that lets you look inside the box.

![An incubator made of dark stained wood is mounted on a stand of black stained wood carved with decorative waves. The lid has a built-in glass plate that lets you look inside the box.]() The Norwegian Museum of Sience and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

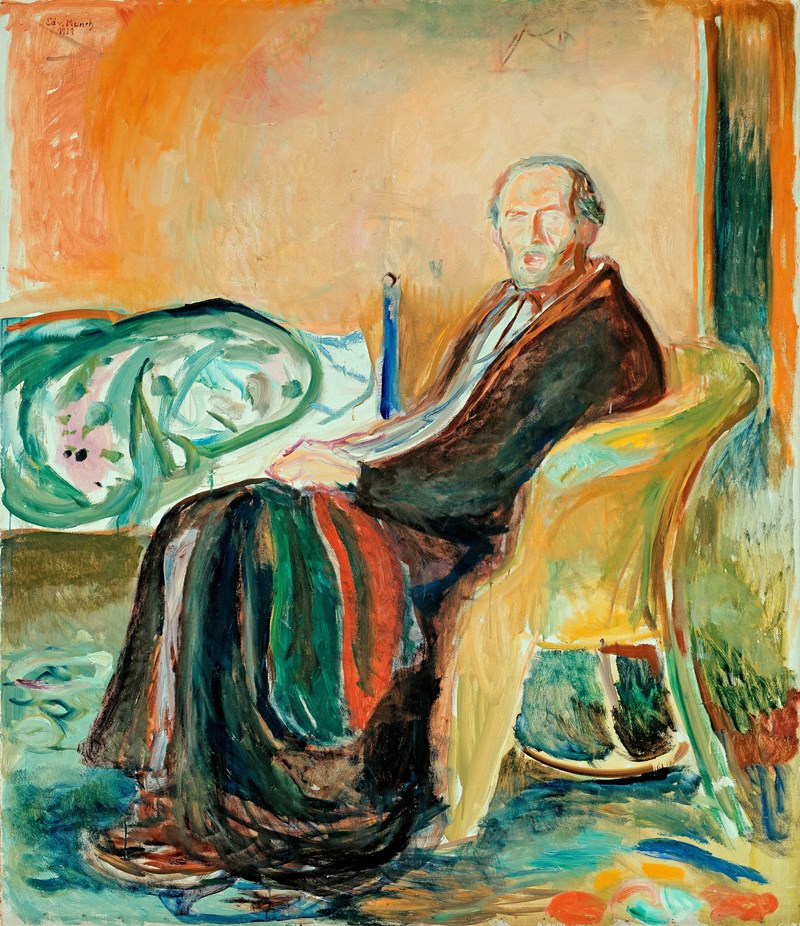

The Norwegian Museum of Sience and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, MunchmuseetPainting by Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919

Edvard Munch, wearing pyjamas and a dressing gown, is seated in a wicker chair. The chair is yellow and Munch sits with a red and green blanket on his lap. He is in a bedroom, and his unmade bed can be seen in the background.

Context: Sick Self-Portraits

Early in his career, Edvard Munch became known as a painter of illness. But up until about 1900, he mostly depicted other people suffering from health problems. This changed dramatically as he approached middle age, and especially after his hand surgery in 1902. From then on, he more frequently depicted himself as a sick man. Munch often made these new self-portraits on large canvases, with vibrant colours and bold expressive brushstrokes. These works offered a dramatic contrast between sickness and health.

![]()

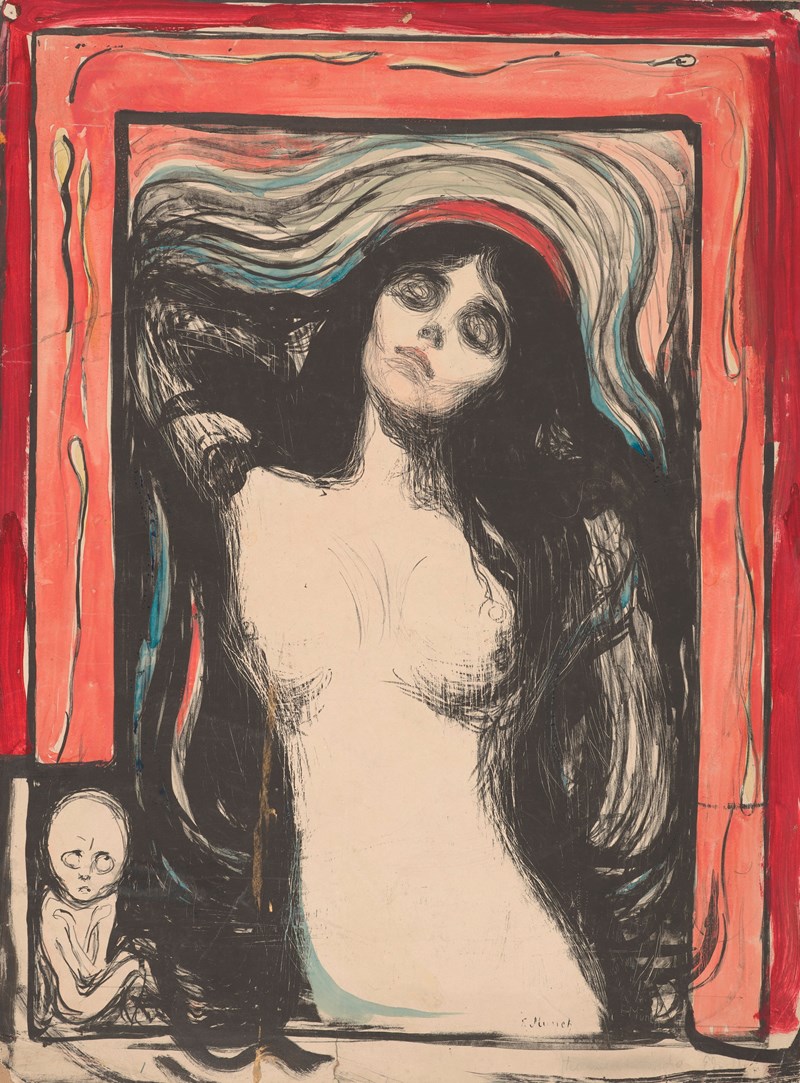

Lithograph by Edvard Munch: Madonna, 1895

A dark-haired, nude woman stands with her right hand in her hair and her left hand behind her back. She wears a red hat pushed back on her head, which resembles a halo. The image is framed by a red-coloured border, with a foetus and sperm cells as decoration.

Context: Sex and Reproduction

Around 1900 Edvard Munch made numerous works depicting women and men with floating sperm and foetuses. In Madonna, one of his most popular and widely reproduced prints, the woman can be seen as experiencing orgasm, as a sacred mother figure or even as a corpse. Death and the Woman depicts a woman dancing with death. These works linked sex and pleasure to their potentially tragic consequences, just as debates over reproduction, contraception and abortion were becoming increasingly political.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Foster Mothers in Court (also known as Angel Makers), 1902

Inside a courtroom, several seated men are talking and pointing at five women in the dock. They are foster mothers accused of taking in illegitimate children for a fee, then neglecting the child until it dies. A large crowd watches the proceedings from the public gallery.

![]()

Sanitary Health Sponge, 1920s

An old sanitary sponge with a matching tin case. The case is yellow and worn, and is decorated with red crosses and a red circular border frame. Text on the lid reads ‘Sanitary Health Sponge’ in Gothic script.

Context: Eugenics

The pseudo-science of eugenics was widely discussed and accepted in the early 20th century. Blending genetics with racial politics, it promoted selective breeding to ‘purify’ the human gene pool by eliminating those deemed ‘undesirable’. In many countries, eugenics became official policy, most notoriously in Nazi Germany. Figures like Marie Stopes, a women’s rights and sex education advocate, backed birth control and even sterilisation for the ‘unfit’ or ‘racially diseased’. Katti Anker Møller in Norway and Margaret Sanger in the United States held similarly complex views. These were echoed in the marketing of contraceptives in the 1920s and 30s. Although eugenics is today discredited as science, its influence can still be felt.

![An old sanitary sponge with a matching tin case.]() Private Collection. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

Private Collection. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet -

Room description:

The exhibition space is painted in a light yellow colour and is located behind a horizontal wall that gives visitors two possible entrances, each 2.6 metres wide. Behind this is a horizontal wall containing both display cabinets and paintings. Towards the room’s exit is another horizontal wall that runs parallel to the walls of the exhibition space. On the front, there are a total of six works, as well as a rectangular window. To the rear, next to the wall, visitors have the option of sitting or lying on a wave-shaped ergonomic bench. At the end of the room, a corridor 3.1 metres wide leads visitors into the final exhibition space.

Room theme text:

Edvard Munch had a lifelong fascination with the vices and excesses of the big city. For years, he drank heavily, which added to his existing health problems. When he felt that his nerves were fraying, he would escape to seaside towns, spas and sanatoriums where he could recharge and restore his health. In these places, he could soak up the sunlight and breathe fresh sea or mountain air. But these resorts sometimes had their own ‘unhealthy’ temptations. When Munch travelled to the French Riviera in search of a warmer climate, he also found himself drawn to the bars and roulette tables of Monte Carlo.

Painting by Edvard Munch: Still Life with Tomatoes, Leek and Casseroles, 1926–30

A large dish of tomatoes and leeks stands on a kitchen bench. Scattered around the dish are a wooden spoon, two large aluminium cooking pots and a smaller saucepan. In the background you can see a wall with stripy wallpaper, and two semi-circular windows.

Context: The Vegetarian Munch

Around 1900, when Edvard Munch was in Berlin, the city’s vegetarian restaurants were part of Germany’s ‘Life Reform’ movement. Life Reformers reacted against industrialisation and urban problems by promoting a ‘back to nature’ philosophy, a vegetarian, alcohol- and tobacco-free diet, exercise, nudism, and alternative spiritualities. Munch was practically a vegetarian for much of his later life. He ate mostly plant-based foods, fish, and very little meat. One of his drawings links meat-eating to animal cruelty. He teased his friends about joining him in this lifestyle: ‘As a member of the vegetarian sect I say repent! from cannibalism. Eat not your uncles, aunts and little cousins… but, like the lamb, eat lilies, lily-of-the-valley and grass’. Here, Munch links vegetarianism with physical and spiritual purity.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Naked Figures and Sun, 1924–25

Eleven naked human figures are sitting, lying and standing, while beams from a small red sun stream over the scene. Trees are visible in the background. The figures are loosely painted, almost blending into a landscape of wavy brushstrokes.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: At the Roulette Table in Monte Carlo, 1892

In a casino, a crowd of people is gathered around a roulette table. The men are in evening dress, and some women are wearing fashionable headgear with feathers and veils. A green lamp illuminates the scene from above the table. Some gamblers lean over the table to place their chips, while others stand by, making notes.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Kristiania Bohemians, possibly 1907

Four men are sitting around a table in a smoky bar. They are dressed in suits and coats, and the man at the front right of the image is wearing a bowler hat. On the table are several bottles and glasses of alcohol. In the background are several indistinct figures.

![Kristiania Bohemians: Four men sit around a table with bottles of alcohol and glasses. Shadows emerge from behind them in a hazy blue atmosphere.]()

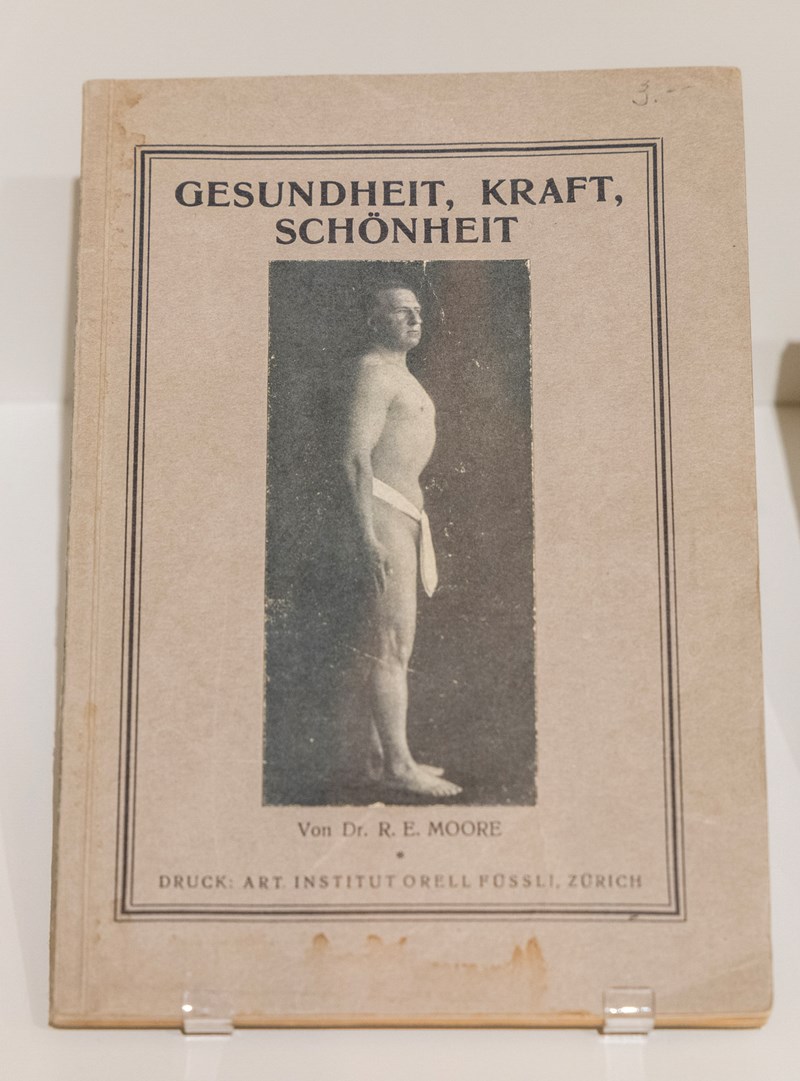

Publication by R.E. Moore: Health, Strength, Beauty, 1923

A pamphlet in yellowed paper, showing its age. In the black and white cover photo, a naked man is depicted from the side, with a loincloth hanging from his waist. Above the photograph is the German title ‘Gesundheit, kraft, schönheit’. The author and Swiss publisher are named below the picture. These are framed by a border of three thin stripes.

![A pamphlet in yellowed paper, showing its age. In the black and white cover photo, a naked man is depicted from the side, with a loincloth hanging from his waist.]()

Sound:

In this room you can hear a soundscape of illustrative and atmospheric sounds.

Description of the sound:

You hear the sound of water dripping, and someone washing and scrubbing skin. Gentle electronic music begins to play. The music fades into the sound of someone chopping vegetables and squeezing fruit juice. This fades into rumbling casino chatter. Someone turns a handle, and you hear tinkling coins. Playing cards are shuffled and dealt out. Betting chips rattle against each other. A hatch closes. After another electronic music interlude, the sounds fade out and are replaced by wind blowing and someone walking on creaking ground. Branches snap underfoot and you hear the sound of crunching snow. The sounds fade into children's voices and waves hitting the shore. Electronic music marks a transition, before you hear hissing and a steam locomotive starting slowly before picking up speed. The train slows down and fades away, while the sounds of cicadas, grasshoppers, frogs and gusts of wind take over. The insect noises transition into water dripping, washing and scrubbing, while the electronic music plays out.

-

Room description:

The final two themed sections of the exhibition are separated by a cross-shaped intersection of a longer and shorter wall in the centre of a larger space. The right half of this area is Room 7, and is painted in a matt light brown. There is no seating in this section.

Room theme text:

In late 1889, Edvard Munch was studying art in Paris when he learned that his father had died. Overcome with grief, he doubted whether he could carry on ‘with this miserable body, polluted with medicine...’. The main doctor figure in his life – his father – was gone. But he soon came to know other doctors, as personal friends and artistic patrons.

Many doctors bought works from Munch, and he sometimes arranged payment for healthcare with art rather than money. Owning an artwork by Munch was a way for these modern men of medicine to display their good taste. But they were equally invested in Munch’s body. They gave him medical advice and helped him to access healthcare. These ‘great’ medical men were committed to keeping Munch alive and healthy, so that he could carry on creating his ‘great’ works.

Painting by Edvard Munch: Night in Saint-Cloud, 1890

In this darkened room, the only light comes from a window, where pale moonlight casts the shadow of the window frame across the floor. A man sits in silhouette by the window, leaning on his elbow and looking out. He is sitting on a sofa that runs from the window and along the wall. In front of the window hangs an unlit ceiling lamp. A round table can be seen on the right side of the room, but is cut off halfway by the frame.

![]()

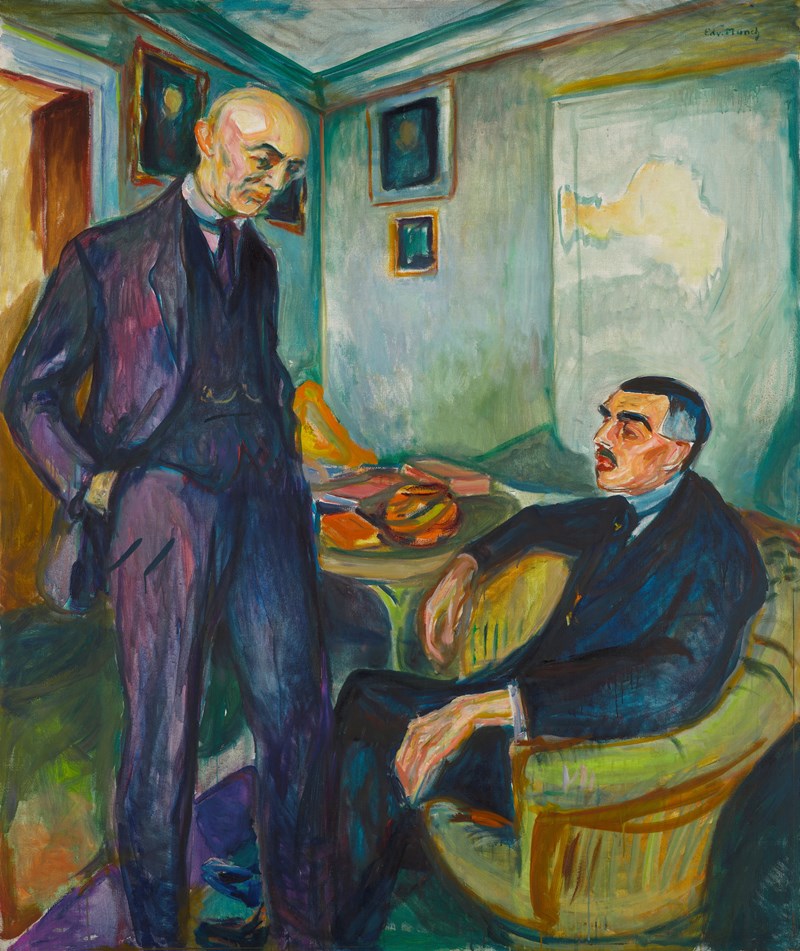

Painting by Edvard Munch: Lucien Dedichen and Jappe Nilssen, 1925–26

Two smartly dressed middle aged men are shown in a domestic room with an armchair and round table. On the walls behind them hang four paintings, and the table is covered with books. The standing man on the left is a portrait of Lucien Dedichen, Edvard Munch’s physician and personal friend. He is bald and stands with his hands in his pockets, looking down at the dark-haired man sitting in the chair on the right. He is Jappe Nilssen, a writer and art historian who had just been diagnosed with a terminal illness.

![]()

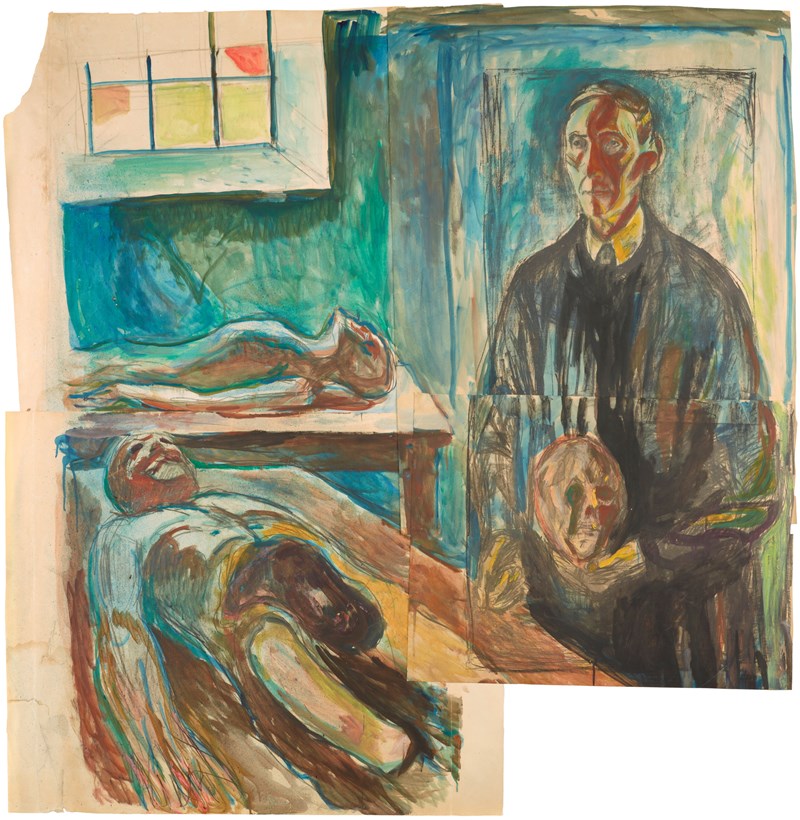

Lithograph and watercolour collage by Edvard Munch: Anatomy Professor Kristian Schreiner, 1928–32

This motif is a collage of four sections of wove paper fastened together, with visible misalignments where the edges meet. Professor Kristian Schreiner, who was Edvard Munch’s personal doctor, stands in a long black coat in a blue painted hospital morgue. A window can be seen high on the wall in the background. Shadow covers half the man's face, and in his hands he holds a human head. In front of him under the window lie two corpses on dissecting tables. The corpse in front of him has had its left leg amputated at the hip and the right leg cut off at the knee.

![]()

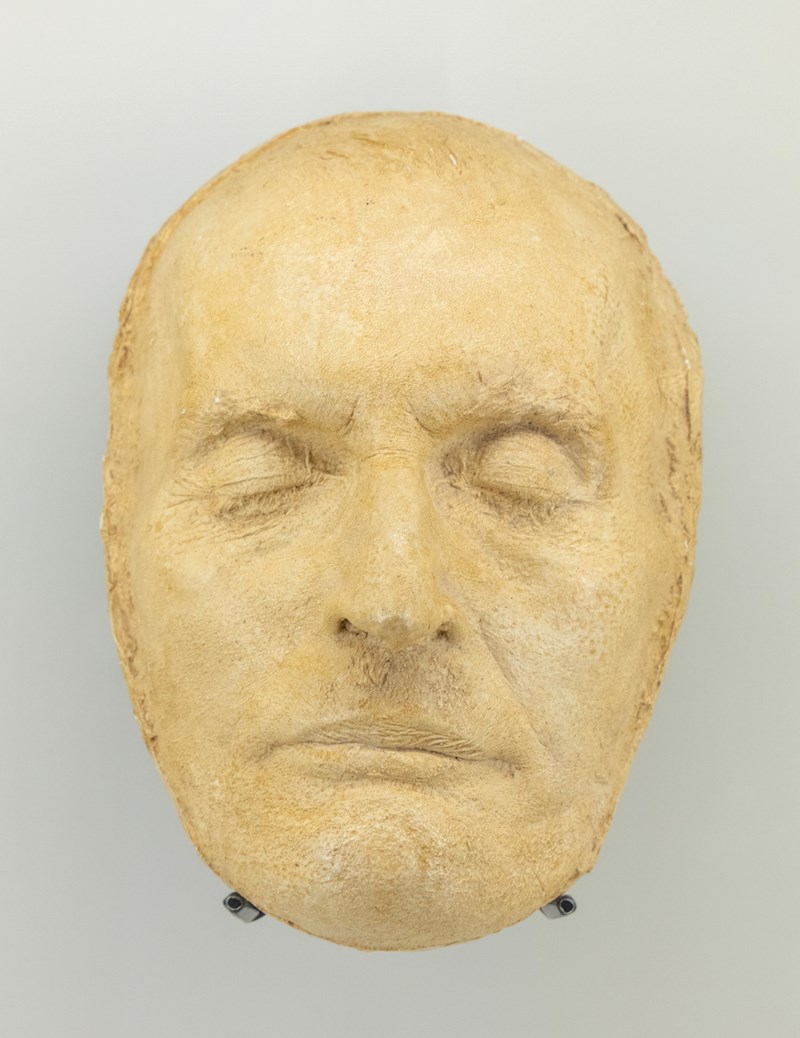

Edvard Munch’s death mask, 01.02.1944

A plaster of Paris mask moulded from Edvard Munch’s face shortly after his death in 1944.

![A three-dimensional plaster mould of Edvard Munch’s face.]()

‘Vibraphone’ hearing aid, 1923–40

A small leather case, lined with a white silk fabric printed with the words ‘European Vibraphone Co. Triumph House, 189-181, Regent St. London, W.’ In the base of the box is a purple velour cushion, which holds a silver hearing aid. It is engraved with the number ‘8448’. This hearing aid belonged to Edvard Munch's sister, Inger Munch.

![A small leather case, lined with a white silk fabric. In the base of the box is a purple velour cushion, which holds a silver hearing aid.]() The Norwegian Museum of Sience and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet

The Norwegian Museum of Sience and Technology. Photo: Ove Kvavik, Munchmuseet -

Room description:

The themed section ‘Care’ occupies the other half of the larger space, and is painted in a similar light brown to Room 7. A display case with a height of 0.97 metres sticks out from the sloping long wall and is adapted to be visible to wheelchair users. In the centre of the room is a curved bench 1.9 metres long. A 2.5 metre passageway leads to the exit.

Room theme text:

Edvard Munch was struck down by a health crisis in autumn 1908. Drinking made him paranoid, parts of his body became paralysed and he began hallucinating. His friends advised him to take a break. He checked into a private nerve clinic in Copenhagen for a seven-month course of rest, pine needle baths, massage and electrotherapy, under the care of Dr. Daniel Jacobson. The clinic’s staff encouraged him to keep making art during his stay.

Most caregivers at the clinic were women. Many were trained nurses, pursuing careers in the male dominated field of medicine. Their daily tasks, including intimate contact with patients, sometimes exposed them to uncomfortable or even dangerous situations. While in treatment, Munch made many images of the staff, suggesting care as a complex experience for both the patient and the caregiver.

Munch eventually left the clinic with a new understanding of the need to rest and recharge whenever he felt sick. During Munch’s lifetime, caregiving shifted from the home to the hospital, from the private realm to the public sphere. Despite its many challenges, care is the lifeblood of every community and society. Whether given one-to-one or delivered by an institution, care changes the world for all of us.

Painting by Edvard Munch: Nurses Holding a Sheet, 1909

Two women in white nursing uniforms stand in a room with yellow walls. Both have brown hair tied back. The woman on the right holds a sheet outstretched. In front of them hang more sheets. They are looking at something off to the right, outside the frame.

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Man and Woman by the Window with Potted Plants, 1908–11

A man is standing at the left of the motif, stubbing out a cigarette. He is wearing a dark blue suit and overcoat. To his left, in the centre of the painting, is a woman in a white dress with a blue sash around her waist. Her face is red and she is looking straight at the viewer. They are standing in front of a window, and a dark night sky can be seen outside. On the windowsill are two potted plants with pink flowers.

![]()

Modern copy of a photograph by Edvard Munch: A Nurse at the Clinic, Copenhagen, 1908–09

A woman models for the photo seated in a chair with her hands in her lap, wearing a long white dress belted at the waist. Her hair is up and she is looking away from the camera. Other artworks by Munch can be seen in the background, with a painting on the wall and one standing on an easel.

![]()

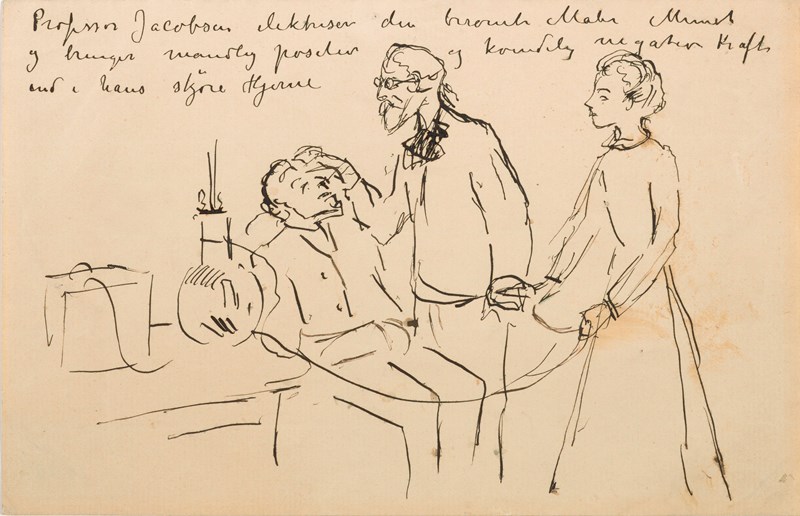

Ink drawing by Edvard Munch: Munch at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic, 1908–09

Edvard Munch leans back in a chair at Dr Daniel Jacobson's clinic. Dr Jacobson stands over him, examining his forehead with one hand. A nurse stands nearby. The drawing shows Munch about to receive electro therapy. A text in Munch’s handwriting appears over the motif. Translated, it says: ‘Professor Jacobson electrifies the famous painter Munch and brings masculine positive and feminine negative strength into his fragile brain.’

![]()

Painting by Edvard Munch: Daniel Jacobson, 1908–09

A full length portrait of Professor Daniel Jacobson, standing in a yellow room, with a red curtain behind him to the right. He is wearing a brown suit, with a blue scarf around his neck and a gold chain in his waistcoat pocket. He stands with hands on hips, pushing back the flaps of his jacket. The room is lit from the front, casting a strong black shadow behind Jacobson.

![]()

-

The exit from the exhibition is a narrow corridor painted in the same red colour as was used in the first room. The sound of a beating heart can be heard as you pass through the exit.

Listen to the sound from the room (opens in external player).

What did you think?

Did you enjoy Lifeblood – Edvard Munch? Your feedback is vital for us to continue producing the best possible exhibitions and experiences. Please take a moment to fill in our audience survey (takes approx. one minute).